Anemia is a widespread global health issue, with iron deficiency being the most common cause. However, rare genetic conditions, such as aceruloplasminemia, also contribute to unexplained cases. Aceruloplasminemia, a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by systemic iron accumulation, is typically diagnosed in adulthood at advanced disease stages when treatment efficacy is limited. Here, we report a novel case of an 11-year-old girl-the youngest confirmed pediatric patient to date-presenting with persistent microcytic hypochromic anemia, low serum iron, markedly elevated serum ferritin, and evidence of hepatic and cerebellar iron deposition. After common causes of anemia were excluded, whole-exome sequencing revealed a homozygous splicing mutation in the ceruloplasmin gene (NM_000096.3: c.147-2A > G), which was classified as likely pathogenic according to ACMG/AMP guidelines. Pedigree analysis revealed that the parents of the affected child are carriers of the mutation. Functional validation confirmed that this mutation led to exon 2 skipping, disrupting the ceruloplasmin structure and abolishing its copper-binding sites. Following iron chelation therapy, the patient remained clinically stable over a three-year follow-up period, with no progression of organ iron overload. This case underscores the importance of considering aceruloplasminemia in pediatric patients with refractory microcytic anemia, particularly when accompanied by low serum iron and disproportionately elevated ferritin levels. Early genetic screening and intervention may help prevent irreversible complications associated with this rare disorder.

Keywords: Ceruloplasmin (CP), Homozygous mutation, Anemia, Acinetobacter pneumoniae

Aceruloplasminemia is a rare autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the Ceruloplasmin (CP) gene, leading to the absence or defect of ceruloplasmin ferroxidase activity. The resulting impairment of iron export from cells causes systemic iron overload, particularly in the brain, liver, and pancreas, which contributes to a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations, including retinal degeneration, diabetes mellitus, and progressive neurological disorders. Typically, patients first present with anemia-often microcytic and refractory to conventional treatment-long before the onset of diabetes or neurological symptoms, emphasizing the critical importance of early diagnosis and intervention.1,2 Neurological manifestations, such as movement disorders (including blepharospasm, grimacing, facial and cervical dystonia, tremors, and chorea) and ataxia (gait disturbance, dysarthria), closely correlate with iron accumulation in specific brain regions. Moreover, cognitive dysfunction-manifesting as apathy, memory impairment, and reduced executive function—occurs in more than half of affected individuals.3-5 While most reported cases are diagnosed in adulthood, often when irreversible organ damage has occurred, pediatric cases with early-stage diagnoses remain exceedingly rare.4

In this study, we report a unique case of an 11-year-old girl who presented with recurrent microcytic hypochromic anemia, physical stunting, and cognitive impairment. After comprehensive exclusion of common causes of anemia-including iron deficiency anemia, α- and β-thalassemia, hematological malignancies, and peptic ulcers—a homozygous splicing mutation in the CP gene (NM_000096.3: c.147-2A > G) was identified via whole-exome sequencing. Pedigree analysis revealed that the parents of the affected child were carriers of the mutation. The pathogenicity of this variant was confirmed through bioinformatics analysis and functional validation via a minigene splicing assay. Notably, early diagnosis allows timely initiation of iron chelation therapy, leading to clinical stabilization over a three-year follow-up without progression of organ iron deposition. This case highlights the diagnostic significance of considering aceruloplasminemia in pediatric patients with unexplained refractory microcytic anemia, particularly when accompanied by paradoxically low serum iron and elevated ferritin. Our findings underscore the value of early genetic screening and intervention in altering the disease course and preventing severe complications associated with systemic iron overload.

Patient evaluation and diagnostic workup

An 11-year-old girl with a four-year history of persistent microcytic hypochromic anemia (hemoglobin 81–96 g/L) was admitted for evaluation. The patient had no history of surgery, trauma, or infectious diseases. Physical examination revealed pallor of the skin and sclera; normal skin elasticity and temperature; and no signs of rash, hemorrhage, or lymphadenopathy. Laboratory investigations included a complete blood count, serum iron studies, iron metabolism marker analysis, and hemoglobin electrophoresis. To exclude common causes of anemia, including iron deficiency anemia, α- and β-thalassemia, hematologic malignancies, and peptic ulcer disease, a comprehensive diagnostic panel was performed. α- and β-Thalassemia gene testing was carried out, along with bone marrow aspiration cytology, to assess hematopoietic activity and iron status. Abdominal Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Computed Tomography (CT) were performed to evaluate potential organ iron deposition. Additionally, cranial MRI, ophthalmologic examinations, blood glucose measurements, and plasma ceruloplasmin quantification were conducted. Whole-exome sequencing was performed to identify potential genetic abnormalities associated with the patient’s clinical presentation.

Whole exome sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients via a Qiagen DNA Mini Blood Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The Roche KAPA HyperExome probe set captured exons and adjacent splicing regions for sequencing on the MGISEQ-2000 platform. The raw data were processed and aligned to the hg19 reference genome via standard bioinformatics tools (SOAPnuke, BWA, and GATK). Variants were screened and annotated via public databases (ClinVar, OMIM, HGMD, 1000 Genomes Project, gnomAD, and ExAC) and classified according to ACMG/AMP guidelines.

Sanger sequencing

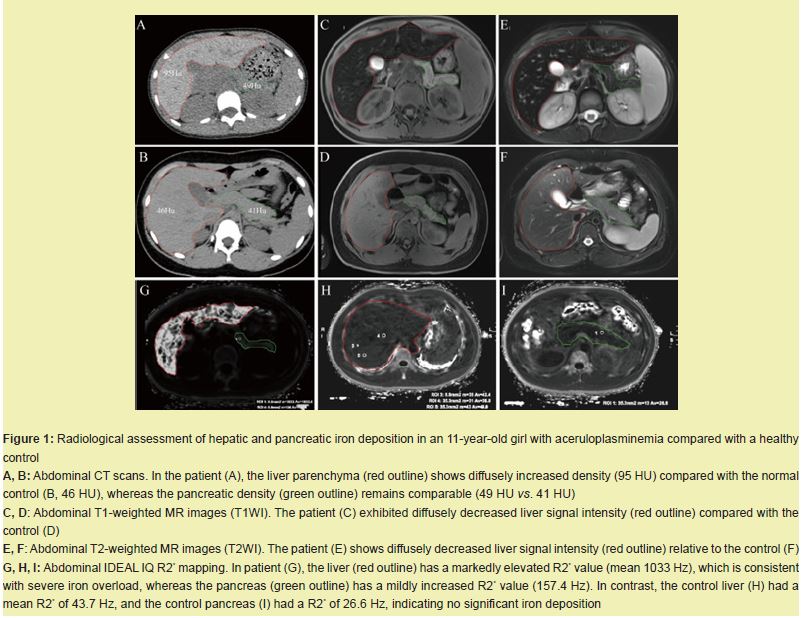

Mutations were analyzed via direct sequencing of all coding exons and exon‒intron boundaries of the Ceruloplasmin (CP) gene, including at least 50 base pairs of flanking intronic sequences. PCR primers were designed via Primer3 version 0.4.0 (https://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/primer3, last accessed July 10, 2025) Supplementary Table 1. The PCR products were purified and subjected to bidirectional Sanger sequencing. The sequencing results were aligned and compared to the reference sequence of CP (GenBank accession number NM_000096.3) and reviewed manually to identify potential pathogenic variants.

Bioinformatics and Splicing Analysis

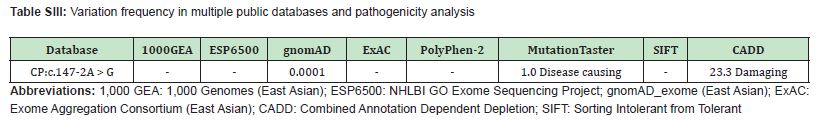

Pathogenicity was predicted via bioinformatics tools (PolyPhen-2, MutationTaster, SIFT, and CADD). Splicing effects were evaluated via an RNA splicing prediction model from the Guangzhou Rare Disease Gene Therapy Alliance. Protein structure changes due to mutation were modeled via SWISS-MODEL. Protein structure visualization was performed via PyMol (v3.1.0a0 Open-Source, https://github.com/cgohlke/pymol-open-source-wheels/releases).

Minigene analysis

To evaluate the effect of the CP c.147-2A > G splicing variant on pre-mRNA processing, we performed splicing assays via a pCAS2-based minigene system containing CP exon 2 with its flanking intronic regions. Wild-type and mutant constructs were generated and transiently transfected into HEK293T cells. Total RNA was extracted after 48 hours, followed by RT-PCR to assess splicing outcomes. Aberrant transcripts were analyzed via agarose gel electrophoresis and verified via Sanger sequencing. The primer sequences are provided in Table SI.

Clinical findings and diagnostic outcomes

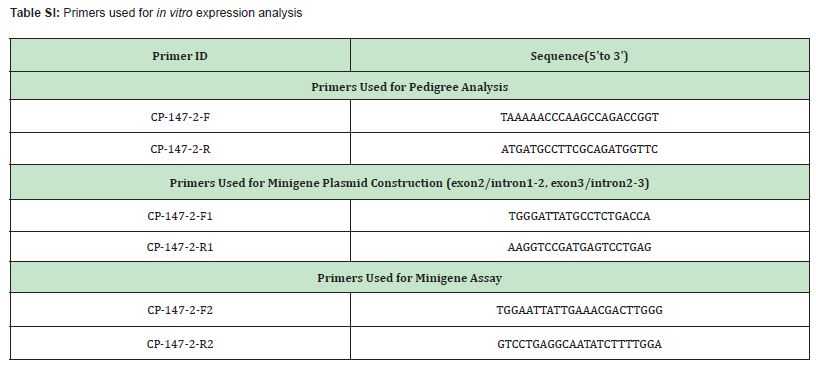

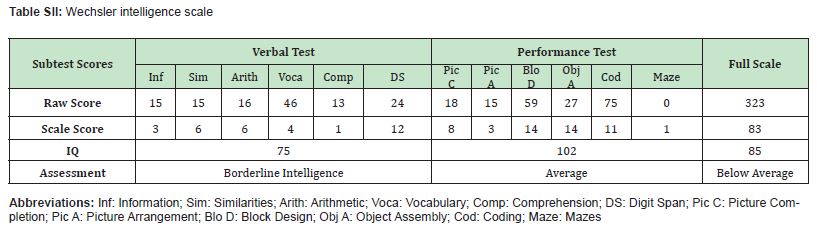

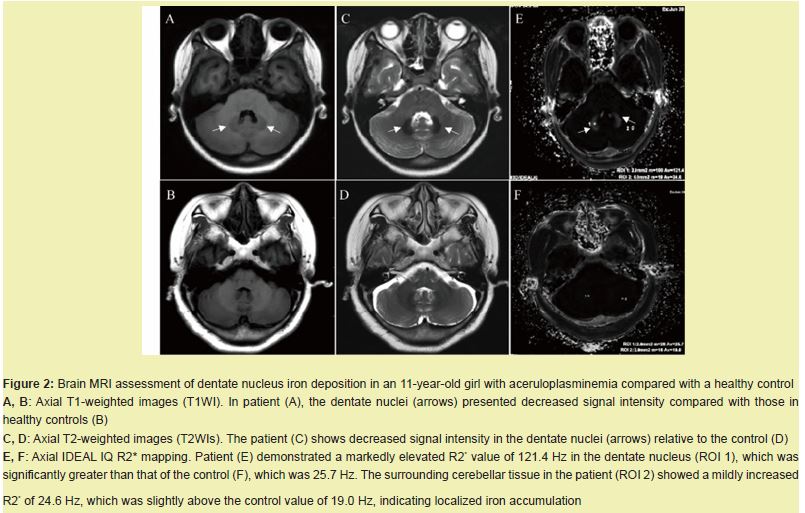

The patient exhibited low serum iron (3.8 μmol/L; reference range: 9.0-32.3 μmol/L), markedly elevated serum ferritin (1585 μg/L; reference range: 12-150 μg/L), and low transferrin saturation (9.39%; reference range: 20%-50%). She also presented with growth retardation, poor concentration, and low cognitive performance Table SII. Temporary improvement in hemoglobin was noted after iron supplementation, but anemia relapsed repeatedly. α- and β-Thalassemia gene analyses revealed no pathogenic variants. Bone marrow aspiration cytology revealed active granulocytic and erythroid proliferation, with increased numbers of immature and granular megakaryocytes. The intramedullary iron level was elevated, whereas the intramedullary iron level remained within the normal range. Abdominal MRI revealed diffusely prolonged T1 and shortened T2 signals in the liver parenchyma, which was consistent with iron deposition Figure 1. The cranial MR image revealed mild iron deposition in the dentate nucleus of the cerebellum Figure 2. Blood glucose and ophthalmologic assessments were normal. The plasma ceruloplasmin levels significantly decreased (< 20 mg/L; reference range: 210-530 mg/L). Whole-exome sequencing revealed a homozygous splicing mutation in the CP, suggesting that aceruloplasminemia was the underlying cause of the patient’s anemia and systemic iron overload. To investigate the molecular and imaging features associated with aceruloplasminemia in the proband, we performed a comprehensive analysis including abdominal imaging, brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), and functional validation of the CP gene mutation.

Hepatic and pancreatic iron deposition detected by CT and MRI

Abdominal CT revealed diffusely increased liver parenchymal density in the patient (95 HU), which was markedly greater than that in the healthy control (46 HU), while the pancreatic density remained comparable (49 HU vs. 41 HU) Figure 1A,B. On MRI, the patient showed diffusely decreased liver signal intensity on both T1-weighted Figure 1C,D and T2-weighted images Figure 1E,F relative to that of the control, which was consistent with iron overload. Quantitative R2* mapping by IDEAL-IQ further confirmed significant hepatic iron deposition, with a liver R2* value of 1033 Hz in the patient and 43.7 Hz in the control. A mildly elevated pancreatic iron content (157.4 Hz vs. 26.6 Hz) was also noted Figure 1G–I.

Iron accumulation in the cerebellar dentate nucleus on brain MRI

Brain MRI revealed bilaterally decreased signal intensity in the dentate nuclei on T1-weighted and T2-weighted images in the patient compared with the normal control Figure 2A–D. IDEAL-IQ R2* mapping revealed a markedly elevated R2* value of 121.4 Hz in the patient’s dentate nuclei, which was significantly greater than the control value of 25.7 Hz. The surrounding cerebellar tissue also showed mildly increased R2* (24.6 Hz vs. 19.0 Hz) Figure 2E,F. These findings indicate pathological iron accumulation in the cerebellar dentate nucleus.

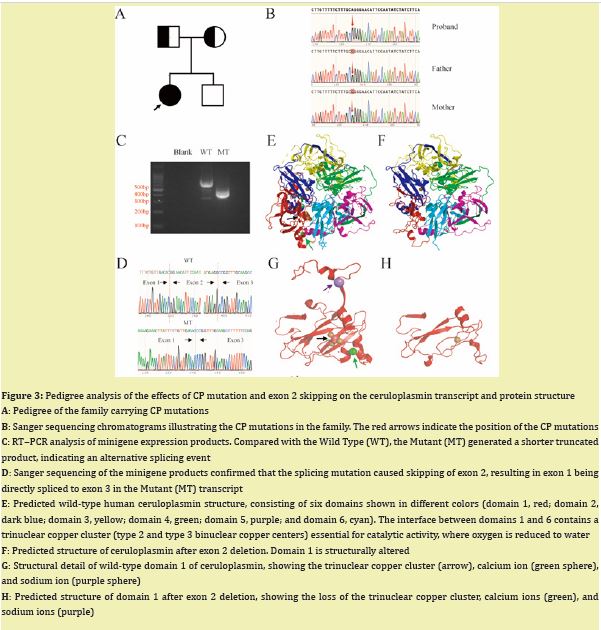

Exon 2 skipping caused by splicing mutation disrupts the CP structure

A homozygous splicing mutation in the CP gene (NM_000096.3: c.147-2A > G) was identified via whole-exome sequencing. Pedigree analysis revealed that the parents of the affected child were carriers of the mutation Figure 3A, 3B. Variation frequencies in multiple public databases of mutations are extremely rare or absent in the general population (1000 Genomes Project, ESP6500, gnomAD_exome, ExAC). Bioinformatics analysis (PolyPhen-2, MutationTaster, SIFT, and CADD) predicted both mutations as pathogenic Table SIII. RT‒PCR analysis of minigene expression demonstrated that the splicing mutation led to a truncated transcript in the mutant compared with the wild type Figure 3C. Sanger sequencing confirmed that the mutation resulted in exon 2 skipping, causing exon 1 to be spliced directly to exon 3 Figure 3D. Structural modeling of wild-type human ceruloplasmin revealed that its six-domain architecture is stabilized by a trinuclear copper cluster located at the interface between domains 1 and 6 Figure 3E. Deletion of exon 2 resulted in a predicted structural disruption of domain 1, abolishing the trinuclear copper cluster and the associated calcium- and sodium-binding sites Figure 3E-H. This structural alteration likely impairs the ferroxidase activity of ceruloplasmin, contributing to systemic iron overload.

Treatment and prognosis

The child was started on oral deferasirox dispersible tablets at 20 mg/kg/day. A follow-up visit 2 weeks after discharge revealed the following: hemoglobin 98 g/L (increased from baseline); mean corpuscular hemoglobin 20.2 pg; mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration 277 g/L; mean corpuscular volume 73.1 fL; reticulocyte percentage 0.82%; and ferritin 1,255 ng/mL (decreased from baseline). All the values improved, and the patient was under regular outpatient follow-up at our hospital. The current dose of deferasirox dispersible tablets has been reduced to 10 mg/kg/day for treatment.

We report an 11-year-old girl with genetically confirmed aceruloplasminemia—the youngest documented to date. She presented with refractory microcytic hypochromic anemia, growth delay, and mild cognitive impairment. Laboratory studies revealed paradoxically low serum iron and markedly elevated ferritin. Whole-exome sequencing revealed a homozygous splice-site variant, c.147-2A > G, in the Ceruloplasmin Gene (CP). Pedigree analysis revealed that the parents of the affected child are carriers of the mutation.CP has six structural domains with a three-copper catalytic center, one Ca+ binding site, and one Na+ binding site, all of which are essential for its oxidative function6 and protein stability.6,7 The c.147-2A > G variant disrupts the canonical acceptor splice site. Minigene assays revealed complete skipping of exon 2 Figure 3C, 3D. Structural modeling revealed that this deletion disrupts the trinuclear copper cluster bridging domains 1 and 6, eliminates both Na⁺- and Ca²⁺-binding sites Figure 3E-H, abolishes ferroxidase activity, and explains the undetectable serum ceruloplasmin (< 20 mg/L) and pronounced early iron loading Figure 1,2.

A summary of the clinical manifestations and age of onset in 71 Japanese individuals revealed that 80% of patients under 20 years of age presented iron-restricted microcytic anemia. With advancing age, approximately 76% of individuals experience retinal degeneration, 70% are diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, and approximately 90% of patients with ceruloplasmin deficiency exhibit neurological symptoms after an average of 12.5 years of insulin-dependent diabetes.1 The clinical presentation of anemia prior to the onset of diabetes or neurologic symptoms is common in patients with aceruloplasminaemia, highlighting the importance of early genetic screening for accurate diagnosis.

Our report advances the earliest age of confirmed diagnosis by at least a decade and positions aceruloplasminemia within the differential diagnosis of pediatric anemia. Although symptoms are typically described between the third and eighth decades of life.8 this case demonstrates that symptomatic disease can manifest in early childhood. Under physiological conditions, ceruloplasmin—or its intestinal counterpart hephaestin-oxidizes ferrous iron exported by ferroportin; this reaction is required both for safe loading onto transferrin and for the surface stability of ferroportin itself.6,9-12 In the absence of functional ceruloplasmin, ferroportin is rapidly internalized and degraded.13,14 Ferrous iron accumulates within hepatocytes, reticuloendothelial macrophages and eventually the central nervous system, whereas transferrin saturation decreases.15-17 These pathophysiological changes generate an iron profile that is easily misread as common iron deficiency anemia, with one crucial exception. In classic iron deficiency, serum ferritin is the first marker to decrease, followed sequentially by serum iron and transferrin saturation.18 In aceruloplasminemia, serum iron is low (reflecting impaired export), but ferritin is paradoxically elevated because intracellular iron cannot be mobilized. Thus, any child presenting with microcytic anemia, low serum iron and high or normal ferritin-especially if unresponsive to oral iron-should undergo immediate CP gene analysis. Early recognition not only averts unnecessary and potentially harmful iron supplementation but also allows timely institution of iron-chelation therapy and positions the patient for emerging enzyme- or gene-replacement strategies, thereby reducing the long-term risks of diabetes, retinal degeneration and irreversible neurodegeneration.

Iron chelation therapy is currently the cornerstone treatment for aceruloplasminemia. The small lipophilic chelator deferiprone crosses the blood–brain barrier to capture deposited Fe²⁺ and promote its urinary or biliary excretion.19 whereas the hydrophilic chelator deferoxamine or oral deferasirox primarily clears hepatic and splenic iron.20,21 In this case, the child received oral iron chelation therapy. The short-term response has been favorable: anemia has improved, and serum ferritin has decreased. However, the duration of treatment remains brief, and the long-term efficacy is still uncertain; therefore, repeated reassessment of this patient is needed.

Given that this was a single case, the generalisability of our findings is limited; multicenter pediatric registries are needed to validate the full genotype–phenotype–imaging–treatment pathway. In addition, functional validation was restricted to an in vitro minigene assay and in silico modeling; patient-derived cells or animal models would provide in vivo confirmation. Finally, long-term neurocognitive follow-up remains preliminary. Future studies should incorporate standardized neuropsychological batteries and quantitative brain iron imaging to assess the true impact of early intervention on neurological outcomes.

In summary, aceruloplasminemia caused by CP, c.147-2A > G, can present in childhood with isolated anemia. Early genetic diagnosis coupled with iron chelation therapy effectively halts systemic iron accumulation. We recommend including CP in routine genetic panels for children with unexplained microcytic anemia who have disproportionately elevated ferritin and depressed serum iron levels to enable early diagnosis, timely treatment, and improved long-term outcomes.

The data generated in the present study may be requested from the corresponding author.

Xin Tan, Qin Huang, Li Bai and Jin Su are responsible for the clinical work, including patient recruitment, obtaining informed consent, and sample collection. Yuxin Li conducted the CT and MRI examinations. Xin Tan conceived and designed the experiments, whereas Ying Wu and Xiao Liu executed the experiments. Ying Wu, Xiao Liu, Jin Su and Li Bai drafted the primary manuscript. Xin Tan reviewed and revised the manuscript. Funding was obtained from Xin Tan, Yuxin Li and Jin Su. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript. Xin Tan confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data.

This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of The Affiliated Changsha Hospital of Xiangya School of Medicine, Central South University, with the approval number [(2025)Ethical Rapid Review NO.22] and the approval date [20250916].

All adults participating in this study provided written informed consent. For minors, written informed consent was provided by their parents.

Patient consent for publication was obtained from all participants. For minors, written informed consent was provided by their parents.

The privacy rights of human subjects are strictly protected in this study. All personal information of the subjects has been anonymized.

No generative AI or AI-assisted technologies were used in the preparation of this manuscript.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation - Medical and Health Sciences Joint Fund (2025JJ80480), Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation Project: Dosing Strategy and Drug Resistance Mechanism of Azithromycin against Mycoplasma pneumoniae Infection in Children Based on Intrapulmonary Pharmacokinetic Characteristics and Metabolomics (2025JJ80486). The Changsha Municipal Health Commission Scientific Research Program (KJ-A2023006) and the Ideological Education Reform and Practice in Standardized Residency Training: A Trinity Integrated Cultivation Model of Knowledge-Ability-Value (2025CSSKKT74).

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

- 1. Miyajima H. Aceruloplasminemia, an iron metabolic disorder. Neuropathology. 2003;23(4):345-350.

- 2. Kang HG, Kim M, Lee SC. Aceruloplasminemia With Positive Ceruloplasm Gene Mutation. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(7):e160816.

- 3. Najoua Maarad, Mounia Rahmani, Adlaide Taho, et al. Neurodegeneration With Brain Iron Accumulation in a Case of Adult Aceruloplasminemia. Cureus. 2024;16(8):e67331.

- 4. Xu WQ, Ni W, Wang RM, et al. A novel ceruloplasmin mutation identified in a Chinese patient and clinical spectrum of aceruloplasminemia patients. Metab Brain Dis. 2021;36(8):2273-2281.

- 5. Marchi G, Busti F, Lira Zidanes A, et al. Aceruloplasminemia: A Severe Neurodegenerative Disorder Deserving an Early Diagnosis. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:pp.325.

- 6. Bento I, Peixoto C, Zaitsev VN, et al. Ceruloplasmin revisited: structural and functional roles of various metal cation-binding sites. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2007;63(Pt 2):240-248.

- 7. Sato M, Gitlin JD. Mechanisms of copper incorporation during the biosynthesis of human ceruloplasmin. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(8):5128-5134.

- 8. Miyajima H. [Aceruloplasminemia]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2000;40(12):1290-1292.

- 9. De Domenico I, Ward DM, di Patti MC, et al. Ferroxidase activity is required for the stability of cell surface ferroportin in cells expressing GPI-ceruloplasmin. EMBO J. 2007;26(12):2823-2831.

- 10. Vashchenko G, Macgillivray RT. Functional role of the putative iron ligands in the ferroxidase activity of recombinant human hephaestin. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2012;17(8):1187-1195.

- 11. Dlouhy AC, Bailey DK, Steimle BL, et al. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer links membrane ferroportin, hephaestin but not ferroportin, amyloid precursor protein complex with iron efflux. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(11):4202-4214.

- 12. Vulpe CD, Kuo YM, Murphy TL, et al. Hephaestin, a ceruloplasmin homologue implicated in intestinal iron transport, is defective in the sla mouse. Nat Genet. 1999;21(2):195-199.

- 13. Ross SL, Tran L, Winters A, et al. Molecular mechanism of hepcidin-mediated ferroportin internalization requires ferroportin lysines, not tyrosines or JAK-STAT. Cell Metab. 2012;15(6):905-917.

- 14. De Domenico I, Ward DM, Langelier C, et al. The molecular mechanism of hepcidin-mediated ferroportin down-regulation. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(7):2569-2578.

- 15. Levi S, Finazzi D. Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation: update on pathogenic mechanisms. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:99.

- 16. Brissot P, Ropert M, Le Lan C, et al. Non-transferrin bound iron: a key role in iron overload and iron toxicity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1820(3): 403-410.

- 17. Wang RH, Li C, Xu X, et al. A role of SMAD4 in iron metabolism through the positive regulation of hepcidin expression. Cell Metab. 2005;2(6):399-409.

- 18. Camaschella C. Iron-deficiency anemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(19):1832-1843.

- 19. Vroegindeweij LHP, Boon AJW, Wilson JHP, et al. Effects of iron chelation therapy on the clinical course of aceruloplasminemia: an analysis of aggregated case reports. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15(1):105.

- 20. Stumpf JL. Deferasirox. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(6):606-616.

- 21. Badat M, Kaya B, Telfer P. Combination-therapy with concurrent deferoxamine and deferiprone is effective in treating resistant cardiac iron-loading in aceruloplasminaemia. Br J Haematol. 2015;171(3):430-432.