Homophobic bullying in schools affects the sense of safety and belonging of LGBT youth in the school community, with several impacts. We know that homophobic bullying has consequences, but it is important to understand the mechanisms underlying these consequences, and how we can mitigate some of these consequences. We know that we cannot erase bullying, but there are ways to reduce and/or mitigate its effects. The goal of this research was then to understand what variables (e.g., a sense of security and a sense of belonging) could explain the impacts of bullying, and what variables in a school context we could intervene with. Thus, an online questionnaire was used and 562 participants from Portugal (15 to 21 years old) participated. The results showed that the sense of safety of LGBT youth mediates the relationship between homophobic bullying and absenteeism, as well as academic performance. It was also possible to conclude that the feeling of belonging mediates the relationship between bullying and the student's low self-esteem. The results and implications for education policy are discussed.

Keywords: Homophobic bullying, Feeling of security and belonging, Absenteeism, Academic performance, Self esteem

Although any student may suffer from bullying, there is enough evidence supporting that the students most likely to experience this type of behaviour are all those who are observed as non-heterosexual, such as young LGB individuals (UNESCO, 2012).1

In this sense we speak of homophobic bullying, i.e., a specific type of bullying, that although there is no consensus on its definition, the main characteristics (e.g., beliefs, attitudes, stereotypes, negative actions and consequences) may explain homophobic victimization.2 This type of bullying is associated with bullying in general (e.g., physical, verbal, direct or indirect aggression) but covered with homophobic content.3According to O'Higgins-Norman,4 homophobic victimization can be divided into two subtypes of behavior: bullying that sustains the heteronormativity of the school environment, alluding to expectations of gender roles (male vs. female); and bullying that presupposes direct harassment of young LGBT people (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender).5

The prevalence of homophobic bullying in schools is evidenced by a variety of national and international studies that reveal the magnitude of this phenomenon. If we look at the international context, the records of bullying are high.6-7 A US study revealed that 88.9% of gay youth heard the term "gay" used in a derogatory manner, 40.1% were physically assaulted and 18.8% were assaulted.7 Another study indicated that 55.5% of LGB students stated that there were discriminatory practices in their school and that 65.2% had already experienced them.8 In turn, according to António,3 homophobic behavior occurs more frequently outside of school (67%) than in the school grounds/recreation (28%). Besides, boys had the highest average level of psychological violence and victimization (56.1%) when compared with girls.3

Low self-esteem, absenteeism, poor academic performance are some examples of the outcomes of homophobic bullying.9-12 Varjas and employees12 support this data by demonstrating in their study that young people from sexual minorities who suffer homophobic victimization are four times more likely to avoid school as a result of victimization. Robinson, Bansel, Denson, Ovenden and Davies,13 in their study of the school environment in Australian schools, showed that young victims of homophobic bullying had lower levels of class concentration (32.6%), worse subject scores (23.5%) and absenteeism (21.4%).

School environment and homophobic bullying

Nevertheless, several studies have shown that schools are among the social spaces where LGB youth are more likely to suffer from verbal and physical homophobic abuse than those suffered in their community or at home.14 According to Goodboy and Martin,15 education is the most effective resource for preventing homophobic bullying. However, schools now provide education based on beliefs, prejudice, and the transmission of heteronormative ideologies to children and young people, making education one of the leading causes of homophobic bullying, as children and young people use this learning in interactions with their peer groups.15

In the recent decades, school environment has indicated to be an essential factor in the biopsychosocial and academic well-being of LGB youth and the remaining school community (students, teachers and students).16 In fact, when positive, the school environment is a crucial factor for the success of the student. However, when negative, it can be harmful (e.g., resulting from bullying) by encouraging increased rates of school failure and absenteeism.17 It is clear that students with higher levels of victimization have lower levels of psychological well-being, sense of security, belonging, and school performance resulting from feelings of vulnerability (e.g. fear).1,9,10,13,16,18,19

In Portugal, a study carried out by António and colleagues (2012) pointed out that discrimination based on the heteronormative nature of the school context/environment is present within Portuguese schools, so it is visible that the discrimination experienced by young LGB victims leads to these young people feeling more insecure and less integrated in their school and community.20

It is clear that there are protective factors that, when implemented, can help in reducing and preventing homophobic bullying, such as the implementation of non-discriminatory policies and more inclusive educational curricula.21,22

Rose, Sheremenko, Rasberry, Lesesne and Adkins (2018) stress that schools play a relevant role in creating safe and supportive environments for students, especially young people from sexual minorities. However, the same authors pointed out that LGBT youth are more likely to suffer homophobic victimization and feel more insecure.23 Thus, bullied young people perceive their schools as unsafe, and are therefore more likely to have more difficulty recovering from the traumatic effects of bullying.24

Kosciw, Greytak, Zongrone, Clark and Truong, showed that students felt insecure in school, 59.5% due to their sexual orientation, 44.6% due to gender expression and 35.0% due to their gender. Similarly, the same study showed that 34.8% of LGB students missed at least one full day of school in the last month because they felt insecure.25 Thus, an unsafe and hostile school environment due to victimisation and discrimination at school affects the success at school of LGB students.26

Rivers (2000) showed that LGB students, on average, were more likely to report lower academic performance compared to young heterosexuals. In particular, boys reported a higher prevalence of absenteeism, and lesbian and bisexual girls and bisexual boys reported a higher prevalence of poor grades.27 The victimization experienced by LGB youth in school directly impacts their concerns about their sense of security, which in turn significantly affects their likelihood of absenteeism and their academic performance.27 Thus, the sense of safety of LGB youth has suggest a good mediator in the relationship of homophobic bullying to absenteeism and academic performance of young students:

Hypothesis 1: The feeling of safety mediates the relationship between homophobic bullying and LGB students' absenteeism

Hypothesis 2: The feeling of safety mediates the relationship between homophobic bullying and the academic performance of LGB students

Another important factor is the feeling of belonging to school, and this has been correlated with a growing body of bullying studies conducted regarding LGB youth.13,19,28-30

Robinson, Bansel, Denson, Ovenden and Davies, in their study of a sample of 1032 young LGB Australians, showed that most students experienced some form of victimization in school because of their sexual orientation, in which 59.3% of respondents were socially excluded. Another study showed that LGB youth who perceive themselves as belonging to school tend to feel less stigmatized, manage to create positive relationships with heterosexual peer groups, and have more positive feelings about their sexual orientation compared to those who do not feel included.13,19

Strunz (2015) showed that the feeling of belonging has been correlated with the low self-esteem of young people who suffer from any form of intimidation in a school context.31 This is because the decline in self-esteem of victims of LGBT bullying can be intensified by the fact that these young people often feel that they are not part of the context in which they are placed and therefore have little support from peers or the school community.31 In turn, this systemic lack of belonging, support and fear of stigmatization induces stigmatized young people to increase loneliness, hopelessness and isolation, leading to reduced self-esteem.12 Additionally, Kosciw and employees (2011) showed that higher levels of victimization correlate with lower levels of self-esteem. In this way it becomes pertinent to understand whether homophobic bullying affects the feeling of belonging, which in turn affects the self-esteem of LGB young people. A hypothesis to verify this assumption was therefore explained:32

Hypothesis 3: The feeling of belonging mediates the relationship between homophobic bullying and low self-esteem of LGB students

Participants

The data from this study were retrieved from a more extensive study, the National Study on the School Environment, comprising 663 LGBTI+ students who completed an online questionnaire whose goal was to collect and find out the testimonies of LGBTQI+ young people regarding their experiences in the school context during the last school year.

Nevertheless, considering the objectives of this study, only a few measures of the overall study were used, and participants selected on the basis of sexual orientation. Thus, all individuals whose gender identity did not correspond to the sex that would have been attributed at birth were removed from the final sample. This exclusion criterion was considered since the objective of this study was to study homophobic bullying rather than those issues related to transphobic bullying. Thus, all young people who identified themselves as LGB individuals were selected. After the exclusion criterion was assumed, 562 participants were removed from the final sample and validated.

Of the 562 participants in this study, 98.4% (N = 553) were male Table 1. Age was between 14 and 21 years, with an average of 17.1 years (SD = 1.4). Regarding their sexual orientation 39.6% (N = 213) responded to be bisexual, 26.6% (N = 143) said to be gay and 19.9% (N = 107) responded to be lesbian. In relation to residence area 66.7% (N = 372) said to live in an urban area. The majority attended public school (N = 467, 84.3%) and 79.0% (N = 443) said they were in secondary school.

Procedures

The database used in this study was retrieved from the GLSEN National Study on the School Environment, as previously mentioned. However, in order for the reader to understand all the steps taken, the work developed by the research team stands out a little, before this dissertation appears as a new work proposal.

The questionnaire was initially translated to the Portuguese national context. All questions were translated from the National School Climate Survey provided by GLSEN. After translation, a first collection was carried out at the Arraial Lisboa Pride in 2017 for young LGBTQI+ people regarding their experiences of school victimization. This questionnaire was available on the ILGA Portugal website, between June and August 2017, which could be answered anywhere. In a second phase its dissemination was conducted through paid advertisement on social networks (e.g. Facebook and Instagram) to reach more young people from all over the Portuguese territory. A total of 663 participants were validated, from the population residing throughout the country.

The participants were described using several descriptive statistical measures (percentages, mean, standard deviation and degree of asymmetry). A descriptive analysis of the variables (e.g. homophobic bullying, feeling of belonging, feeling of safety) used in this study was also carried out, as well as its consistency and the correlations between the variables that integrate the analysis model. The data analysis was performed with the SPSS (version 25.0).

The models of mediation and moderation underlying the working hypotheses were tested through PROCESS (Hayes, 2017). The bootstrapping method was thus used to assess the significance of the indirect effect by building the confidence interval for 5000 bootstrap samples.

Instrument and Measures

The National School Climate Survey is a self-reporting instrument built by GLSEN (Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network) in 1999, and used initially in the U.S. and later by schools around the world7,8 in order to evaluate the experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) students in relation to homophobic victimization experiences in schools.33 It should be noted that the version of the questionnaire was adapted to the Portuguese context by the authors of this work.

Then, measures were constructed to test the hypotheses, using a statistical procedure:

Homophobic bullying

Homophobic bullying was operated through ten items rated on a likert 1 (Never) to 5 (Frequently) scale, adapted through the Homophobic Comments section at the National School Climate Survey School in Kosciw and Cullen (1999).33 An example of an item is: "In the last year, how often were you verbally assaulted (through names, threats, etc, directed at you) at your school because of your sexual orientation". Correlations between items range from .20 to .72. Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.82.

Feeling of security

The sense of safety was built from two items relating to the safety of individuals at school, and which were assessed on a point scale ranging from 1 (Frequently) to 5 (Never). An example item is "How often do you feel insecure or embarrassed at your school? The Spearman-Brown coefficient was 0.77.

Feeling of belonging

The feeling of belonging was assessed through five items, with a Likert type scale of 5 points ranging from 1 (I Totally Agree) to 5 (I Totally Disagree). An example of an item is: "I feel like I'm part of the school”. Correlations between items range from .40 to .66, with higher values corresponding to lower levels of feeling of belonging. The alpha coefficient of the five items was 0.84 for feeling of belonging.

Absenteeism

Absenteeism was measured by the question: "During the past month, how many times have you missed class because you didn't feel safe at school or on the way between school and your home?”. Given that most of the participants said they had not missed in the last month (87.7%), the variable showed a high degree of asymmetry (rs = 32.8). In this sense, the statistical treatment of this variable was chosen as a dummy in which zero corresponded to not absent and one to absent at least once.

Academic performance

Academic performance was measured from 1 item "In your last school year, how would you describe most of your grades?", whose response options ranged from 1 (Not satisfactory) to 7 (Excellent).

Low self-esteem

Low self-esteem was measured through a scale about feelings about Yourself with four items, whose response options ranged from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). Correlations between the items ranged from .57 to .74, and the consistency of the new measurement was also meaningful (α = 0.89). Example of an item: "Sometimes I feel really useless".

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

It was possible to verify that 26.2% of the participants (N = 146) stated that they had been "sometimes" verbally assaulted in the last year, and with regard to physical assaults only 4.0% mentioned that "sometimes" these occurred. In relation to other types of intimidation, "sometimes" they were robbed (5.2%), rumors were spread about them (20.5%) and they were excluded because of their sexual orientation (22.2%).

Regarding the places where the participants stated that bullying had occurred and therefore, they felt uncomfortable or insecure, the highlights were the changing rooms (30.8%), toilets (22.8%) and physical education classes (21.0%). It is also worth mentioning that 38.6% of the times in which victimization situations were witnessed by teachers or employees were never intervened. At the same time, when this form of victimization was witnessed by other colleagues, 47.0% said that colleagues never intervened to put an end to the aggression. When the situations were reported, 98.8% of the participants stated that those responsible in the school considered that they should not give importance to what happened, 4.6% revealed that they did nothing to the aggressors the last time they reported harassment or aggression and only 4.6% stated that the aggressor was called attention.

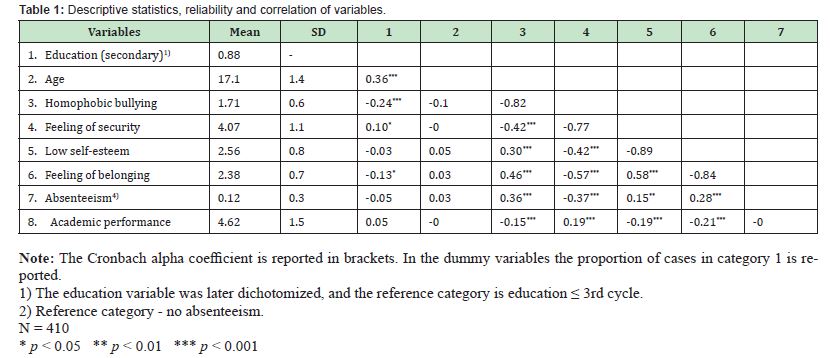

Table 2 shows the mean, dispersion, internal consistency and correlations for the variables under study.

The variable homophobic bullying had a mean of 1.69 (SD = 0.56). For the feeling of safety, the mean was very close to the maximum of the scale (M = 4.06, SD = 1.08). For self-esteem and feeling of presence the averages were relatively similar and were in the middle of the scale (M = 2.56, SD = 0.81 and M = 2.38, SD = 0.46, respectively). Homophobic bullying showed higher correlations (Cohen, 1992) with the feeling of safety (with negative correlation) and with the feeling of belonging (r = -0.42, p < 0.001 and r = 0.46, p < 0.001, respectively). A positive correlation was observed between homophobic bullying and the perception of low self-esteem and also with those who claim to miss more classes (r = 0.30, p < 0.001 and r = 0.36, p < 0.001, respectively).

Mediation of the feeling of belonging and of security

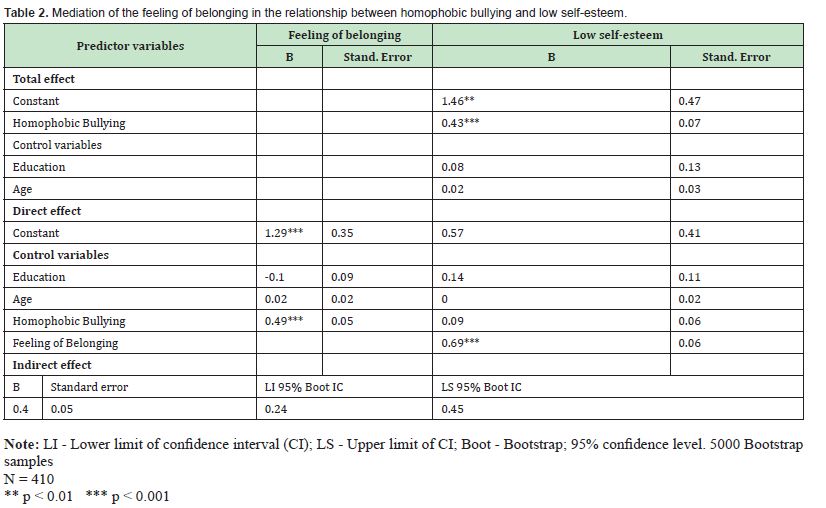

To test hypothesis 3, the mediating effect of the feeling of belonging on the relationship between homophobic bullying and low self-esteem of LGB youth was analyzed Table 2. Homophobic bullying had a significant effect on the perception that LGB youth have of how they feel they belong in a school setting (B = 0.49, t = 10.08, p < 0.001). As this effect was predicted to be positive, the younger people were bullied the more they felt they were not in school. In turn, the sense of belonging to school was significantly related to self-esteem (B = 0.69, t = 12.63, p < 0.001). In this case, the young people who most disagreed with their school membership tended to have a higher perception of low self-esteem. It was also found Table 2 that the indirect effect of homophobic bullying on the low self-esteem of LGB youths was positive and significant (B = 0.36, 95% Boot IC = 0.24, 0.45). The direct effect was not significant (B = 0.09, t = 1.46, p > 0.05) and therefore there was total mediation. Thus, the relationship between bullying and self-esteem can only be explained through the mediating feeling of belonging.

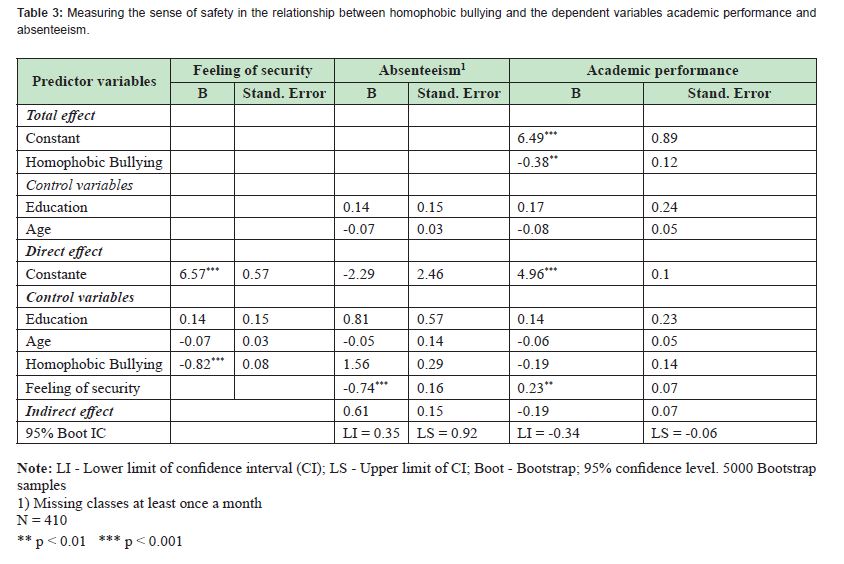

For hypotheses 1 and 2, the mediation of the feeling of safety in the relationship between homophobic bullying and the dependent variables academic performance and absenteeism (absenteeism at least once a month) was tested. A significant negative effect of bullying on LGB youth's perception of their safety at school (B = -0.82, t = -10.28, p < 0.001) was found Table 3. Thus, the more young people have been bullied by others, the less they feel safe in school. There was also a significant effect of the feeling of safety on absenteeism (B = -0.74, t = -4.79, p < 0.001). As expected, young people who tended to feel a greater sense of safety tended to miss school less. The indirect effect was positive and significant (B = 0.61, 95% Boot IC = 0.35, 0.92). Thus, suffering from homophobic bullying had an indirect effect on absenteeism, so this relationship was explained by the mediating feeling of safety. Being bullied also had a significant direct effect on the absenteeism of LGB youth (B = 1.56, Z = 5.32, p < 0.001), so partial mediation occurred.

The mediation effect of the feeling of safety in the relationship between homophobic bullying and academic performance was also tested. In addition to what was previously highlighted in the relationship between homophobic bullying and sense of safety Table 3, a positive effect of sense of safety on academic performance was observed (B = 0.23, t = 3.26, p < 0.01). The significant indirect effect between homophobic bullying and academic performance was also confirmed (B = -0.19, 95% Boot IC = -0.34, 0.06). It was also found that the younger people were bullied, the lower their academic performance; however, there was no significant direct effect on the academic performance of young LGB students (B = -0.19, t = -1.41, p > 0.05), so total mediation occurred. Thus, suffering from homophobic bullying had an effect on academic performance, through mediating a sense of security.

The purpose of this study was to understand which variables (e.g., sense of safety and belonging) could explain the impact of bullying, and which variables in a school context we could intervene in. In this way, the problem of homophobic bullying has been placed in the context of its academic impacts for and of the entire educational environment and school community, expanding the literature regarding the individual effects on young people, on their health, development and well-being.

The results obtained made it possible to verify that the feeling of safety, in this study, had a mediating role in the relationship between homophobic bullying and absenteeism and school performance, in which a role explaining this relationship is confirmed. Thus, the results showed that the more young people are bullied, the less safe they feel at school. In addition, it was observed that the feeling of safety partially affected the relationship between LGB youths who suffer from bullying and miss school at least once a month. Although there is a significant indirect effect of the feeling of safety on youth absenteeism, when the direct effect of bullying on absenteeism is analyzed, it is found that bullying in itself affects the number of absences young people give during one month. Like other studies (e.g. Kosciw 2014), schools that present an unsafe environment for young LGB students mostly end up missing school and classes because they feel insecure.

The feeling of security also played a mediating role in the relationship between the bullying suffered by young LGB and academic performance. In this relationship the feeling of safety played a predominant role as there was no direct effect of homophobic bullying on academic performance, so there was only a significant effect on the relationship between the variables through the mediation of the feeling of safety. Thus, this effect is in line with other studies (e.g. Rivers, 2000) in which the victimization experienced by LGB youths in school directly impacts their concerns about school safety, and in turn significantly affects their likelihood of missing classes more often and their academic performance.

As far as the feeling of belonging is concerned, as a mediator of the homophobic bullying relationship in low self-esteem, it has been found, in the first place, that young people who suffer from some form of intimidation at their school tend to feel that they do not belong to their school. However, when we look at the impact of bullying on young people's self-esteem, we find that bullying does not have a significant direct effect on self-esteem, so this relationship can only be explained through the "feeling of belonging" mediator. Thus, this effect goes in the direction of what has been described in the literature, that the more young people are bullied, the less their sense of belonging to school will be (e.g. Diaz, Kosciw, & Greytak, 2010). However, other studies reinforce that the sense of belonging has been shown to correlate significantly with the low self-esteem of young people who are victims of homophobic bullying. This shows us that LGBT youth who feel they are not part of the school context in which they are inserted feel more excluded, less supported, isolated, which in turn affects their self-esteem (e.g. Strunz, 2015). Also, the same author points out that young LGB who do not feel integrated (and low self-esteem) results of a lack of formal and informal support networks (e.g. colleagues, teachers), of integration into a heteronormative culture, and the presence of feelings of rejection and alienation by the family (e.g. Strunz, 2015).31

The results also showed that some/many LGB students have experienced homophobic bullying, and these situations have occurred within the school, especially in the locker rooms or toilets, similarly to other studies that suggest that these locations are conducive to perpetuating acts of victimization, which makes young people feel more insecure (e.g. Kosciw, Diaz, & Greytak).8,10,33,34

With regard to the intervention of the school community in situations of homophobic bullying, it was found that in situations of intimidation witnessed by teachers, staff or colleagues, these never suffered any kind of intervention, and few situations were those in which the aggressor was drawn to the attention of others, as seen in similar studies (e.g. António, 2011).3 In this sense, homophobic bullying still does not seem to be taken seriously and worryingly within Portuguese schools, since it continues to be seen as a common and typical reaction among young people as reported in other studies (e.g. Adams).35

With this study it was possible to perceive that bullying continues to victimize young Portuguese people, based on their sexual orientation and gender expression, and that the feeling of belonging and the feeling of security work as factors that affects the academic performance and self (e.g. self-esteem) of LGB youth, since these factors when affected impact these young people in two fields that are core to their psychosocial development. It is possible to verify that they act as mediators, in which homophobic victimization affects the feeling of security, which in turn affects the academic performance and self-esteem of the young people. In this sense it is pertinent that schools develop primary prevention programs in which the safety of LGB youth is safeguarded through protective measures (e.g. gay-straight alliance group). In addition, it would be appropriate for schools to create formal and informal anti-homophobia support networks so that young people could feel integrated and above all accepted as they are and for who they are.

There are some limitations regarding this study, namely in the collection of data, since the sample was collected though a convenience method given that the objective of the project was to collect the testimony of LGB youth about their experiences of bullying at their school, which made the sample not representative of the Portuguese youth population. Furthermore, this study is based mostly on a male sample, which did not allow other statistical tests to be conducted which would allow other data to be extracted and better explain this phenomenon. Another limitation is the fact that this study was based only on self-reporting measures, so it would be interesting, for example, in partnership with schools, to actually have the number of absences that the students had in a month or even their academic performance during the year. Also, the questionnaire used as an instrument presents few psychometric studies so far. It should also be noted that another limitation is the fact that this study is a correlational study, that although the mediation models tested present significant data and it is possible to make significant predictions and infer that the variables correlate, it is not possible to test the causality of the effect.

In future studies, it becomes pertinent that this model could be replicated with other youth populations, namely young transsexuals, where they are explored around the topic of transphobic bullying. It would also be interesting to identify what dimensions of the inclusive curriculum affect young people's sense of safety and what practices or even policies affect the safety and well-being of LGB students. It would be relevant in future studies, for example by modeling structural equations, to observe how homophobic bullying, or any other form of bullying that affects the sense of belonging (e.g., colleagues, teachers, staff) of LGBTQI+ youth, which in turn encourages isolation, exclusion, which in turn leads to low self-esteem, and whether the low self-esteem of these youth has an impact on the development of psychological suffering (e.g., depression).

None.

This Research Article received no external funding.

Regarding the publication of this article, the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.