SCI is a devastating condition characterized by the loss of motor, sensory, and autonomic function, with limited treatment options. This paper reviews the physiological architecture of the healthy spinal cord, the pathological mechanisms underlying spinal cord injury, and the current clinical landscape of mechanical and regenerative therapies. Market analysis reveals a growing demand for implantable, programmable, and biologically active solutions as populations age and long-term care costs continue to rise. Recent advances in scaffold design, stem cell therapies, neuromodulation, and hybrid technologies are driving innovation in both academic research and commercial development. Together, these trends point toward a future of personalized, multimodal regenerative medicine for spinal cord repair.

Keywords: Spinal cord injury, Tissue engineering, Biomaterials, Scaffold design, Neural regeneration, Regenerative medicine

Abbreviations: SCI: Spinal Cord Injury; ECM: Extracellular Matrix; MSCs: Mesenchymal Stem Cells; PLGA: Polylactic-Co-Glycolic Acid; BDNF: Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor; NGF: Nerve Growth Factor; NT-3: Neurotrophin-3; ES: Electrospinning; FES: Functional Electrical Stimulation; GS: Glial Scar; CAD: Computer-Aided Design; 3D: Three-Dimensional

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a life-altering neurological condition that disrupts communication between the brain and body, often resulting in permanent motor, sensory, and autonomic impairments depending on the injury’s level and severity.1 Each year, tens of thousands of new cases occur worldwide, with the global prevalence estimated at over 27 million individuals living with the chronic consequences of SCI.2

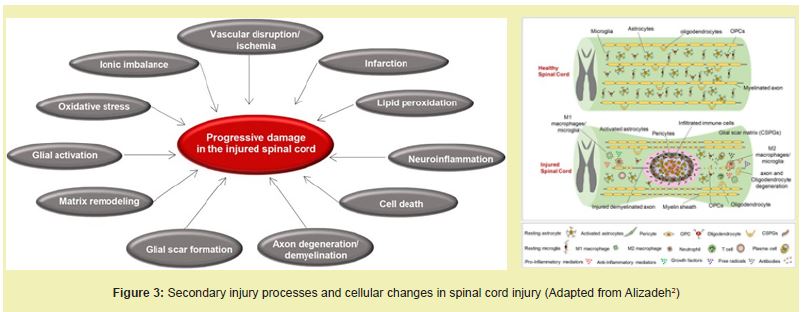

SCI consists of a primary mechanical insult followed by a secondary cascade involving inflammation, ischemia, oxidative stress, and neuronal cell death.3 This secondary injury phase exacerbates tissue damage and leads to the formation of a glial scar, which serves as a major barrier to axonal regeneration.4 Current clinical interventions, including high-dose methylprednisolone administration and surgical decompression, aim to reduce acute inflammation and stabilize the spinal column but offer limited long-term functional recovery.5 These treatments do not address the core biological obstacles to regeneration, such as chronic inflammation, extensive cell loss, and disorganized architecture at the lesion site.6

Tissue engineering has emerged as a promising strategy to overcome these barriers by integrating biomaterials, stem cells, and bioactive molecules to create a permissive environment for repair.7 These regenerative platforms aim to provide mechanical support, guide axonal regrowth, and deliver trophic cues that support neuronal survival and plasticity.8 Recent innovations in hydrogel scaffolds, 3D bioprinting, and stem cell differentiation protocols have enhanced the capacity of tissue-engineered constructs to restore spinal cord architecture and promote regeneration.8 Preclinical models have shown that transplanted neural stem cells can integrate into host tissue, differentiate into neurons and glia, and facilitate partial recovery of motor function when supported by biomimetic scaffolds.9

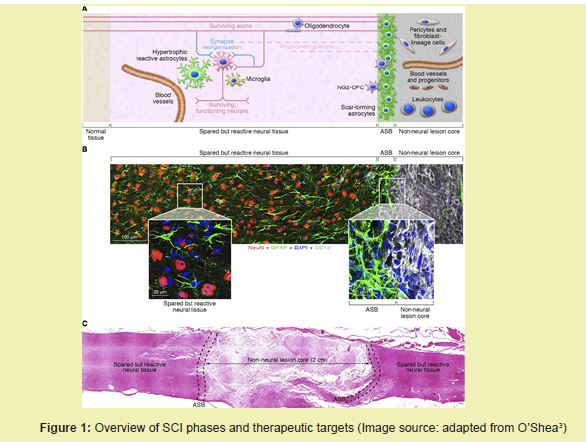

This review will examine the anatomy and physiology of the spinal cord, the pathophysiological progression of , and both current and emerging treatment strategies.2 It will also provide a detailed market outlook and summarize recent clinical pipeline products aiming to restore spinal cord function using tissue-engineered approaches such as stem cell therapies, conductive biomaterials, and neuromodulatory technologies Figure 1.6,8

Healthy spinal cord physiology

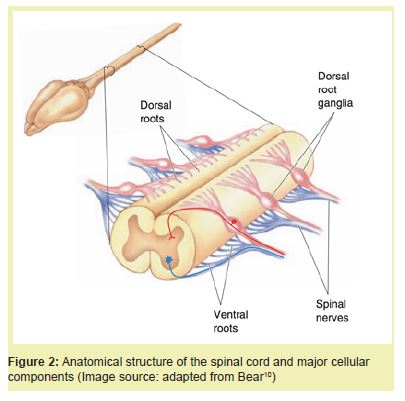

The spinal cord is a cylindrical extension of the central nervous system (CNS) responsible for transmitting motor, sensory, and autonomic signals between the brain and body.10 It is encased within the vertebral column and segmented into 31 regions: eight cervical, twelve thoracic, five lumbar, five sacral, and one coccygeal. Each segment gives rise to a pair of spinal nerves that exit through intervertebral foramina and innervate specific dermatomes and myotomes.11

Structural organization: The spinal cord is composed of an inner butterfly-shaped gray matter core surrounded by white matter.12 The gray matter houses neuronal cell bodies, dendrites, and glial cells, and is divided into dorsal (sensory), ventral (motor), and lateral (autonomic) horns. The surrounding white matter consists of myelinated axons arranged into ascending (sensory) and descending (motor) tracts, including the spinothalamic and corticospinal tracts.12

Like heart valves, the spinal cord possesses layered organization. It is protected by three meningeal layers—the dura mater, arachnoid mater, and pia mater—analogous to the ventricularis, spongiosa, and fibrosa layers in valves.11 Cerebrospinal fluid in the subarachnoid space cushions the cord and facilitates nutrient exchange.

Cellular components: Multiple glial cell types support spinal cord function. Astrocytes regulate extracellular ionic balance and maintain the blood–spinal cord barrier (BSCB), a structure analogous to the blood–brain barrier, formed by endothelial cells, pericytes, and astrocyte end-feet.13 Oligodendrocytes generate myelin sheaths that insulate CNS axons, while microglia function as resident immune cells.

The BSCB selectively regulates the exchange of ions and nutrients and restricts the entry of immune cells and pathogens. Its disruption after injury leads to edema, inflammation, and further tissue damage.13

Functional networks: The spinal cord integrates both conscious motor control and reflexive responses. Central pattern generators located in the lumbar segments control rhythmic locomotion independent of the brain, while reflex arcs mediate rapid, automatic responses to stimuli.10 These functions depend on intact neuronal circuits and are frequently impaired following spinal cord injury.10

Pathophysiology and etiologies of spinal cord injury

SCI results from traumatic or non-traumatic insults that disrupt normal architecture and function. Traumatic SCI typically arises from high-energy events like motor vehicle collisions, falls, or sports injuries and involves compression, contusion, or transection of the cord.1 Non-traumatic SCI stems from internal pathologies such as tumors, vascular lesions, or infections that gradually compress or infiltrate the cord.2

Mechanisms of injury: SCI is typically described in two phases. The primary injury involves immediate mechanical damage such as axonal shearing, hemorrhage, and necrosis.3 This is followed by a secondary injury cascade marked by glutamate excitotoxicity, calcium influx, oxidative stress, and inflammation. Activated astrocytes and microglia contribute to a dense glial scar composed of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs), which inhibit axon regeneration.4 Concurrently, oligodendrocyte loss causes demyelination, and the adult spinal cord's limited regenerative capacity hampers functional recovery Figure 2.6

Etiologies of SCI: Spinal cord injury (SCI) may result from a broad range of causes. Congenital disorders such as spina bifida and tethered cord syndrome lead to structural abnormalities that impair spinal cord function during development.2 Heritable connective tissue diseases, including Ehlers-Danlos and Marfan syndromes, compromise the integrity of spinal support structures, increasing susceptibility to instability and deformation.14 Inflammatory demyelinating conditions like multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica involve immune-mediated destruction of myelin, while systemic diseases such as sarcoidosis can present with similar spinal manifestations.15 Infectious diseases, including tuberculosis, HIV-associated myelopathy, and various parasitic infections, can cause direct damage to the spinal cord, particularly in immunocompromised individuals.2 Neoplasms, whether primary spinal tumors such as astrocytomas or metastatic lesions, may compress the spinal cord and lead to progressive neurological deficits.16 Vascular disorders like anterior spinal artery syndrome or hemorrhagic arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) disrupt spinal cord perfusion, often resulting in sudden and severe functional loss.17 Lastly, degenerative conditions such as spinal stenosis and disc degeneration represent the most common causes of non-traumatic SCI in older adults, as age-related anatomical changes progressively narrow the spinal canal and compress neural elements Figure 3.14

The etiology of spinal cord injury (SCI) encompasses a broad range of underlying conditions, including congenital abnormalities, heritable connective tissue disorders, autoimmune inflammation, infections, vascular lesions, neoplasms, and age-related degeneration.2,15,18 Congenital spinal cord disorders such as spina bifida and tethered cord syndrome arise from incomplete closure or detachment of the neural tube, leading to structural defects and progressive neurological dysfunction.2 These conditions typically present in early childhood and may worsen with growth, often necessitating surgical detethering to prevent permanent damage.2

Heritable connective tissue disorders, including Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and Marfan syndrome, compromise spinal structural integrity by weakening ligaments, discs, and other supportive tissues, increasing the risk of spinal instability and disc herniation.14 These syndromes may also result in spinal deformities such as scoliosis or kyphosis, which can further reduce space within the vertebral canal and predispose individuals to cord compression.14 In rare cases, familial forms of syringomyelia may cause the formation of fluid-filled cavities within the spinal cord, leading to gradual pressure-induced damage over time.14

Inflammatory demyelinating diseases are major contributors to SCI in adults.15 In multiple sclerosis (MS), the immune system targets oligodendrocytes, leading to focal demyelination and impaired nerve conduction.15 Similarly, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) causes recurrent, often bilateral, episodes of transverse myelitis, leading to long-segment cord damage and permanent sensory and motor deficits.15 Sarcoidosis, a granulomatous inflammatory disease, can also affect the spinal cord and mimic other demyelinating conditions.15

Infectious etiologies include tuberculosis (causing vertebral collapse in Pott’s disease), HIV-associated vacuolar myelopathy, syphilitic myelitis, and parasitic infections.2 These conditions are most prevalent in immunocompromised populations or low-resource settings and often present with progressive weakness, incontinence, and spasticity.2 Viral infections like Epstein-Barr virus and herpes zoster virus have also been associated with acute transverse myelitis.2

Neoplastic lesions may be either primary spinal tumors such as astrocytomas and ependymomas or secondary metastases from systemic cancers like breast, prostate, or lung.16 As tumors expand, they compress the spinal cord and vasculature, leading to focal pain, myelopathy, and bowel or bladder dysfunction.16 Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, a rare form of diffuse neoplastic infiltration of the CNS, may present with multifocal spinal cord symptoms.16

Vascular insults such as anterior spinal artery syndrome or arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are among the most acute and devastating causes of SCI.17 These conditions occur when the spinal cord’s blood supply is disrupted by either ischemia, due to blocked arteries, or hemorrhage, due to ruptured abnormal vessels.17 Anterior spinal artery syndrome, for instance, affects the blood flow to the anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord, leading to bilateral motor paralysis and loss of pain and temperature sensation while sparing proprioception.17 AVMs, which are tangled clusters of abnormal vessels, can suddenly rupture, resulting in compressive hematomas or chronic venous congestion.17

The spinal cord’s limited collateral circulation makes it highly vulnerable to even brief interruptions in perfusion.17 Common predisposing factors include atherosclerosis, aneurysms, coagulopathies, and surgical manipulation of the aorta.17 In some cases, patients may present with sudden onset of paraplegia or sensory loss after routine physical activity.17 Chronic venous hypertension caused by spinal dural AV fistulas can also lead to progressive myelopathy, often misdiagnosed until irreversible damage has occurred.17

Degenerative spinal conditions are the most frequent cause of spinal cord injury in aging populations.14 Lumbar canal stenosis, disc degeneration, and ossification of ligaments progressively narrow the spinal canal and compress the spinal cord.14 Over time, this compression leads to chronic myelopathy, sensory deficits, and gait disturbances.14 In elderly patients, symptoms often present subtly and are frequently misattributed to peripheral neuropathy or musculoskeletal disorders, delaying accurate diagnosis.14

Neurological deficits may manifest as weakness, numbness, loss of reflexes, spasticity, or autonomic dysfunction.1 Distinct injury patterns—such as Brown-Séquard syndrome, central cord syndrome, and anterior cord syndrome—help localize the site and mechanism of spinal cord involvement.1 Risk factors for spinal cord injury include advanced age, osteoporosis, autoimmune diseases, infection, and high-impact trauma.2 Patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy are particularly prone to developing central cord syndrome following hyperextension injuries.14

Long-term complications of spinal cord injury include autonomic dysreflexia, urinary tract infections, deep vein thrombosis, respiratory insufficiency, and pressure ulcers, with cervical injuries carrying the highest risk.19 Without proper management, these complications can result in significant morbidity, recurrent hospitalizations, and decreased life expectancy.19 Beyond physical health, long-term care demands, psychological distress, and financial strain amplify the socioeconomic burden of spinal cord injury on individuals, families, and healthcare systems.19

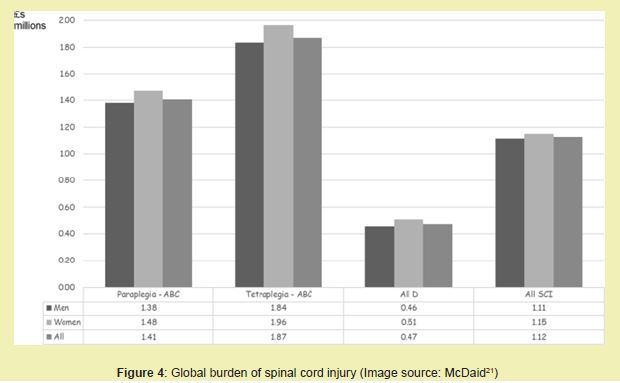

SCI presents a significant public health and economic burden worldwide.20 In the United States alone, it is estimated that approximately 290,000 individuals live with, with nearly 18,000 new cases reported each year.20 As of 2020, the annual direct medical cost of in the U.S. exceeded $9.7 billion, with lifetime costs ranging from $1.6 to $4.9 million per patient depending on injury severity and age at onset.21 As the global population continues to age and survival rates post-injury improve, the prevalence of chronic is expected to increase, driving further demand for long-term care, assistive technologies, and regenerative therapies.2

Globally, incidence rates vary widely, from 13 cases per million in Western Europe to over 163 per million in Southeast Asia, with low- and middle-income countries bearing a disproportionate share of the burden due to higher rates of road traffic injuries and limited access to trauma care.2 Developing regions face additional challenges in managing, including delayed diagnosis, limited rehabilitative services, and high rates of secondary complications.2 These disparities in access and outcome have contributed to an expanding global market for innovative treatment technologies, especially those aimed at improving function and reducing caregiver dependency Figure 4.21

Age remains one of the most significant demographic factors influencing burden and cost.14 As shown in Figure 4, the prevalence of non-traumatic increases significantly in individuals over 60, largely due to spinal stenosis, spondylosis, and degenerative disc disease.14 in older adults is also associated with increased mortality, longer hospital stays, and greater post-discharge care requirements.14 The incidence of incomplete tetraplegia has risen in aging populations due to central cord syndrome caused by hyperextension injuries on a background of cervical stenosis.14

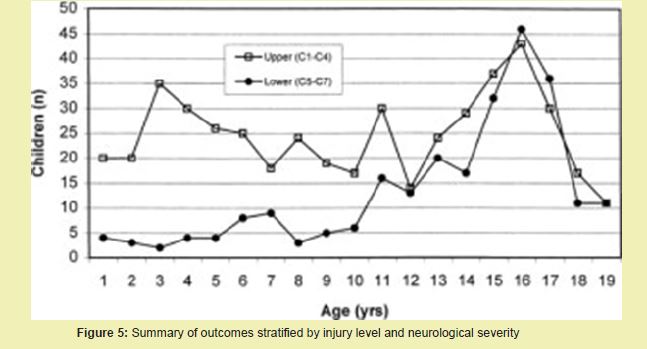

Figure 4 also illustrates the growing need for surgical and non-surgical regenerative solutions as the aging demographic expands.14 Currently, over 50,000 spinal decompression surgeries are performed annually in the U.S. for myelopathy and -related complications.14 As tissue engineering therapies advance into clinical translation, the market for implantable scaffolds, neural stem cell products, and electrical stimulation devices is expected to expand accordingly Figure 5.14

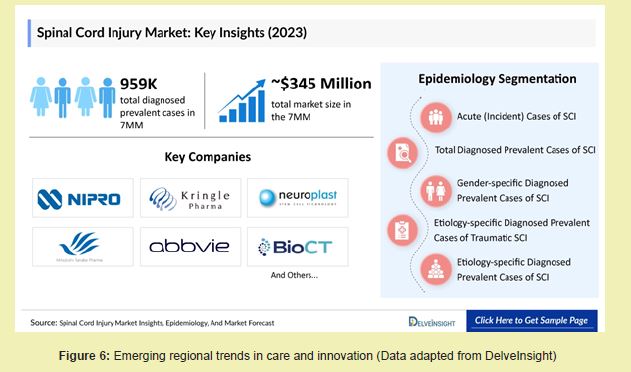

While global economic projections for treatment vary, reports indicate that healthcare systems in high-income countries are steadily increasing investment in management and rehabilitation infrastructure.21 Although North America currently dominates expenditures due to higher treatment costs and specialized care access, regions such as Asia-Pacific are experiencing increasing incidence and growing demand for regenerative solutions.2 Companies and research institutes in these regions are beginning to adopt scaffold-based repair systems, stem cell trials, and neurostimulation platforms, indicating a shift toward more integrative treatment models Figure 6.

Market segments and trends

The SCI treatment market can be divided based on therapeutic type, implant mechanism, and procedure delivery method.6 For therapeutic type, the market consists of mechanical hardware (plates, rods, cages), regenerative biologics (stem cells, scaffolds), and neuromodulation systems (implanted or wearable stimulators).2,22,23 Historically, mechanical hardware dominated management, but the past decade has seen growing interest in regenerative solutions due to their ability to address functional loss rather than just structural realignment.6,24

With the rise in aging populations and increasing incidences of traumatic injury, the demand for less invasive, longer-lasting, and biologically active treatments has grown substantially.23,25 In particular, regenerative therapies such as stem cell infusions and bioresorbable scaffolds are expected to take an increasing share of the global market, which was valued at over $7 billion in 2023 and is expected to grow to nearly $11 billion by 2033.26 Market expansion is driven not only by the increasing patient pool but also by advances in biomedical engineering, government support for neuroregenerative research, and positive clinical outcomes reported from early-phase trials.1,8,27 Additionally, the growing preference for outpatient and ambulatory care has increased demand for technologies that enable low-trauma interventions and reduce surgical complications.28,29 Rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics is also contributing to procedural automation, improved accuracy, and real-time monitoring across minimally invasive platforms.30,31

Increased research into functional electrical stimulation (FES), spinal cord organoid models, and glial scar modulation is enhancing our understanding of lesion recovery and tissue re-integration.32-36 These discoveries are now influencing the design of clinical trials and pushing the development of hybrid solutions that combine real-time feedback with customizable delivery platforms.3,38 For example, companies like BioArctic and ReNetX are developing platforms that use targeted receptor blockers to prevent inhibitory signaling in damaged spinal cord tissue, while implantable pumps deliver neurotrophic agents in a controlled and localized manner.39-41

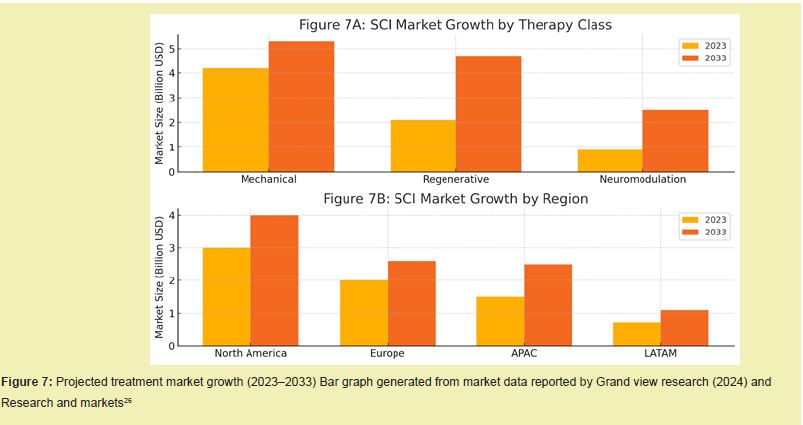

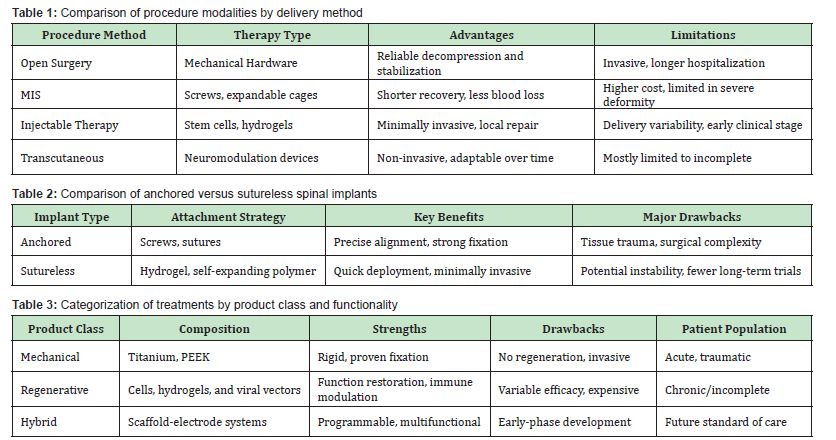

Based on delivery type, therapies can be administered through open surgery, minimally invasive surgical procedures (MIS), injectable therapies, or transcutaneous neuromodulation techniques.15,21 MIS and injectable strategies are increasingly favored in patients with incomplete due to their decreased trauma, reduced recovery time, and enhanced compatibility with combination therapies.42 Open surgical procedures remain necessary for severe trauma, decompression, and multi-level fixation, especially in high-energy cervical or thoracic fractures.1,43,44 However, hospitals are increasingly prioritizing the acquisition of MIS-compatible tools due to their shorter hospital stays, faster return to function, and lower infection rates Figure 7.25

Geographic market dynamics:

The treatment market demonstrates distinct regional trends.26 North America leads in terms of revenue share, driven by high healthcare expenditure, robust reimbursement frameworks, and active clinical trials.31 The United States alone accounts for over 40% of global -related procedure volume, especially in Level I trauma centers.2,25 Europe follows, with Germany, France, and the U.K. showing strong uptake of regenerative products due to government-supported neurorehabilitation initiatives.27,37 In Asia-Pacific, countries like Japan, South Korea, and China are emerging as major players, largely due to expanded infrastructure, local manufacturing, and growing investment in stem cell-based therapies.8,35 Emerging markets in Latin America and the Middle East show slower but steady growth, with cost-effective injectable or neuromodulation platforms gaining preference in low-resource settings.

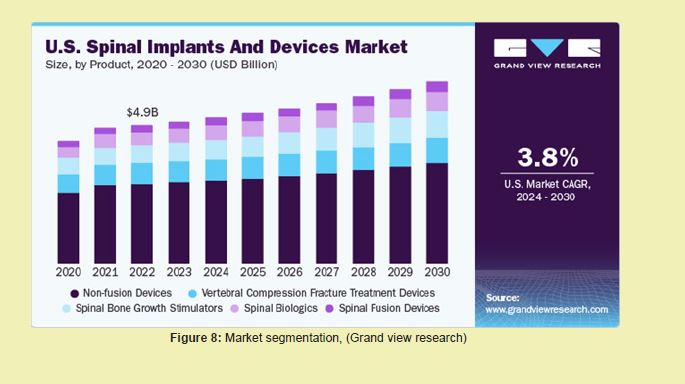

Market forecast and growth trends: As of 2023, the global treatment market is valued at $7.2 billion and is projected to reach $10.8 billion by 2033, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 4.2%.26 The regenerative therapy segment is expected to witness the highest CAGR of 8.6%, particularly driven by stem cell advancements, biocompatible scaffolds, and combination drug-biologic delivery systems.8,27 Neuromodulation devices are also projected to see double-digit growth as wearable, programmable, and adaptive stimulation becomes more mainstream Figure 8.46

Existing products and therapies:

Table 1In addition to the delivery method, device architecture plays a critical role in treatment success.1,26 Implants may be sutured or sutureless, passive or interactive, rigid or bioadaptive.6 Rigid systems, including titanium rods and pedicle screws, remain standard for acute trauma stabilization.14 However, sutureless systems, such as hydrogel-adhesive scaffolds or expandable biointerfaces, are rapidly gaining market traction due to their compatibility with fragile or contused spinal cord tissue.8,37 Furthermore, recent innovations include magnetically guided scaffold positioning, shape-memory polymers, and bioelectronic interfaces that allow scaffolds to expand and conform to lesion geometry after insertion, offering enhanced lesion coverage and spatial fit Table 2.31-35

Mechanical vs. regenerative modalities:

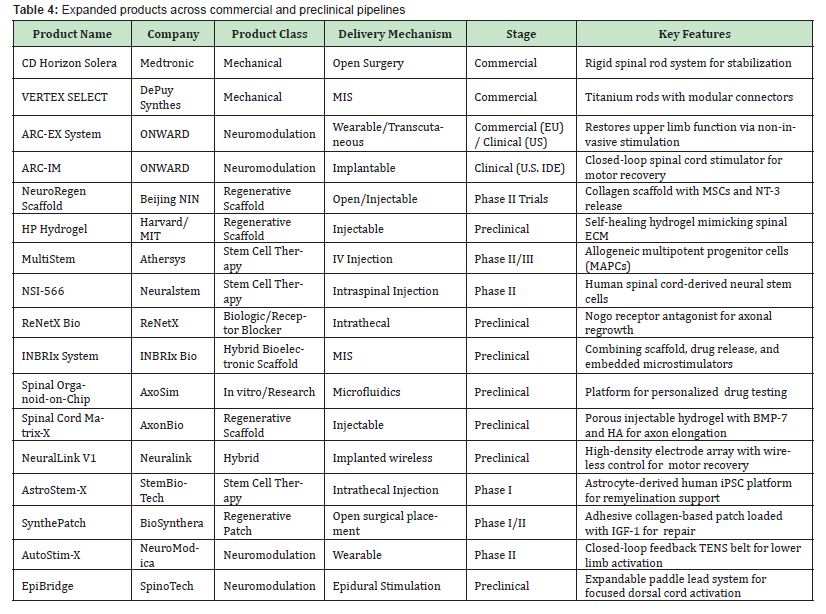

Mechanical systems, such as Medtronic’s CD Horizon Solera spinal rod or DePuy Synthes’ VERTEX SELECT system, are widely used for spinal alignment following injury.14 These systems are composed of titanium or PEEK and offer structural rigidity but do not support neural repair.2 Because of this limitation, they are often paired with decompressive laminectomy in acute.6,25 Mechanical implants continue to be optimized for ease of surgical placement, corrosion resistance, and anatomical conformity.26,31 New generations of implants are being designed to support integration with AI-assisted image-guided navigation platforms, enhancing safety and reducing operating times.9,27

Regenerative products aim to repair lost function via biologically active components.25 Stem cell platforms (e.g., Athersys’ MultiStem or Neuralstem’s NSI-566) are infused or scaffold-seeded to support axonal regrowth and glial modulation.8,33 Hydrogels such as HP-hydrogel and NeuroRegen are engineered to release neurotrophic factors like NT-3 or GDNF while offering a supportive ECM mimic.32 Advanced hydrogel formulations now incorporate microporous networks, nanofibers, and synthetic adhesion ligands to promote axonal sprouting, cell retention, and gradient-based regeneration.27

Furthermore, hybrid products combine bioengineering with device technology, such as the integration of stimulation electrodes within scaffold matrices.33-36 These interactive platforms—still under development—are predicted to dominate the chronic and incomplete segment due to their ability to modulate circuits while supporting regeneration.31,37 Companies like ONWARD, Neuralink, and INBRIx Bio are developing multi-layered scaffolds that simultaneously deliver electrical pulses, drugs, and mechanical guidance cues.47 Researchers are also testing closed-loop systems that provide real-time feedback between electrical activity and scaffold-based nerve interfaces, enabling adaptive neuromodulation that evolves with the healing process.9,36 Such systems hold promise in creating long-lasting synaptic plasticity through activity-dependent remodeling, an approach widely supported in preclinical models of spinal cord regeneration Table 3.6,31

Key commercial and development-stage products

Pipeline products:

Emerging strategies for SCI repair continue to evolve, integrating cutting-edge engineering, material ence, and regenerative medicine.27 In this section, we outline recent advances in prosthetic design, bioengineered scaffolds, and programmable tissue constructs currently in development or clinical trials.34-37 Recent years have witnessed accelerated development in treatment through the emergence of novel implantable, bioengineered, and bioprinted products. Research and development efforts have aimed to enhance efficacy, patient specificity, and long-term integration while reducing invasiveness and complications.8

Among major industry players, ONWARD and Boston entific are advancing next-generation neuromodulation devices with refined delivery and positioning systems for greater targeting precision in patients with partial.33-35 Their devices offer real-time feedback loops, patient-responsive stimulation, and modular attachments that allow for customizable treatment programs. These innovations are especially promising in patients with incomplete injuries were spared neural circuits can be reactivated to restore motor control.47

Additionally, 3D-printed spinal implants have gained traction for their customizable geometry and patient-specific design.31 Institutions such as ETH Zurich and companies like 4WEB Medical are pioneering rapid-manufacture, porous, and bioactive implants made from silicone, PEEK, or titanium-lattice composites. These implants promote osseointegration and neural ingrowth while minimizing the risk of mechanical mismatch or implant rejection.14

3D bioprinting has also emerged as a breakthrough for fabricating patient-customized implants that integrate spatial growth factor gradients and complex cell-loaded topologies.8 Several research teams have demonstrated preclinical efficacy in animal models using multi-material constructs combining collagen, GelMA, and hyaluronic acid.33-37

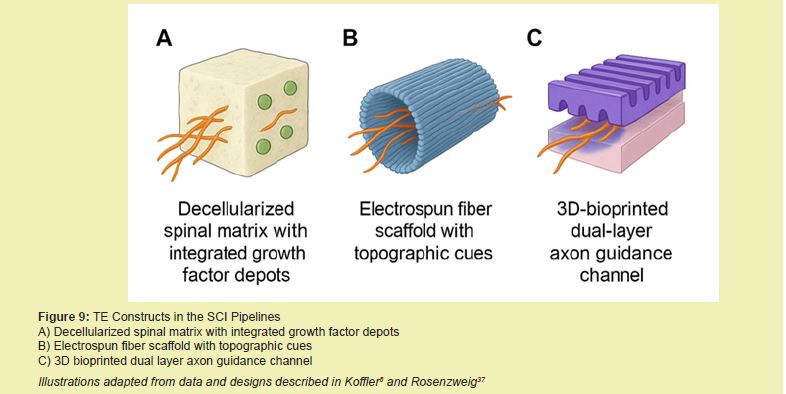

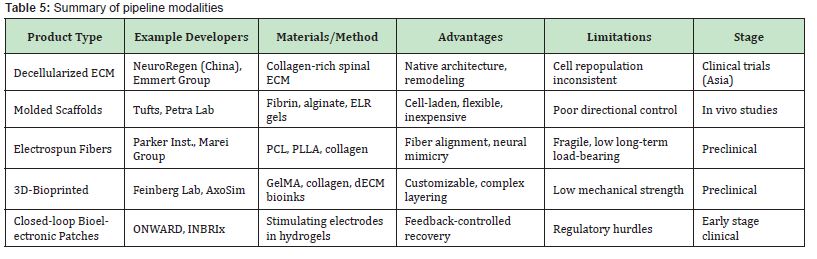

Tissue engineering in aims to replace, regenerate, or restore damaged spinal cord segments through constructs that combine scaffolds, cells, and biochemical cues.34 These tissue-engineered spinal implants (TESIs) offer unique advantages in addressing the regenerative deficit of traditional devices.27

TESIs are typically categorized into decellularized ECM scaffolds, molded hydrogel constructs, electrospun fiber platforms, and 3D-bioprinted implants.37 Decellularized matrices, such as NeuroRegen and CorMatrix spinal patches, offer superior biocompatibility due to native ECM content and porosity but face challenges with recellularization, immune response, and batch variability.8 Despite these challenges, early-stage clinical data from China have shown partial motor and sensory recovery in treated patients.

Hydrogel molding enables heterogeneous layering within one construct. For instance, the Tufts-Petra group created fibrin-alginate gels infused with Schwann cells and MSCs that supported axonal regrowth while withstanding mechanical compression in vivo.34-37 The ability to layer stiff mechanical regions with soft, neuro conductive areas allows tailoring of the scaffold microenvironment to support multiple cell types and tissue integration.27

Electrospinning offers excellent fiber alignment capabilities to mimic spinal tract anisotropy. Composite scaffolds made from polycaprolactone (PCL), poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA), and natural polymers such as collagen or silk have been used to direct axonal regeneration and enhance cell attachment.37 Parker Institute's recent animal model studies show improved functional outcomes compared to blank injury controls.8

3D-bioprinting has rapidly advanced to fabricate spinal patches with compartmentalized architecture, cell gradients, and directional cues. The Feinberg group bioprinted aligned collagen-GelMA conduits with embedded neurotrophic gradients to promote axon directionality.8,48-55 However, challenges with vascularization, mechanical robustness, and printing resolution remain hurdles to widespread application Figure 9, Table 5.27,31,56

SCI remains one of the most devastating conditions in neurology, with limited therapeutic options capable of restoring lost function. Current treatments focus largely on structural stabilization and symptom management, but they do not address the biological barriers to regeneration such as inflammation, demyelination, and glial scarring. Advances in tissue engineering—including biomaterial scaffolds, stem cell therapies, and neuromodulation devices—have opened promising new avenues for repair. Market trends reflect a growing demand for regenerative solutions, supported by strong clinical and preclinical pipelines worldwide. Continued interdiplinary collaboration and investment in translational research will be critical to bringing these therapies into mainstream clinical practice and improving outcomes for individuals living with.

As the field shifts toward regenerative and programmable technologies, future innovations will rely on platforms that integrate responsive biomaterials with embedded sensors, electrical interfaces, or drug reservoirs.27 Tissue engineering is poised to lead the next era of treatment, especially in pediatric and chronic cases where growth, plasticity, and long-term integration are essential.37

However, TE-based approaches must overcome barriers including scalable biomanufacturing, regulatory classification, patient-to-patient variability, and durability under physiological conditions.8 Reproducible cell integration, preservation of directional cues, and reliable host regeneration are essential metrics for future TE implants.36 Additionally, validation under long-term load-bearing, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) exposure, and immune pressure is critical.14,31

Hybrid systems that merge mechanical, chemical, and electrical stimuli, such as smart hydrogel patches with embedded electrodes, will likely dominate the future of repair.27 Long-term studies will be crucial to determine chronic biocompatibility, fatigue resistance, and regenerative capability across different patient populations.25 International collaborations, regulatory clarity, and sustained investment in large-animal and human trials will be essential to move these technologies from bench to bedside.56-60

Ultimately, the future of treatment may lie in a synergistic approach combining structural support, targeted stimulation, cellular therapy, and adaptive, AI-driven modulation to facilitate long-term functional recovery and quality of life.9

Tiya Shah expresses appreciation to Professor Bill Tawil for overseeing the framework of this review, and for the insightful lectures and advice concerning biomaterials and tissue engineering, which contributed to the development of this paper.

There is no funding to report for this study.

Regarding the publication of this article, the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- 1. Ahuja CS, Wilson JR, Nori S. Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2017;3:17018.

- 2. Alizadeh A, Dyck SM, Karimi Abdolrezaee S. Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury: An Overview of Pathophysiology, Models and Acute Injury Mechanisms. Frontiers in Neurology. 2019;10:282.

- 3. O'Shea TM, Burda JE, Sofroniew MV. Cell Biology of Spinal Cord Injury and Repair. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2017;127(9):3259-3270.

- 4. Silver J. Central Nervous System Regenerative Failure: Role of Oligodendrocytes, Astrocytes, and Microglia. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2015;7(3).

- 5. Fehlings MG. Cell-Based Therapies for Spinal Cord Injury. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2018;14(12):679-694.

- 6. Assinck P. Cell Transplantation Therapy for Spinal Cord Injury. Nature Neuroscience. 2017;20(5):637-647.

- 7. Struzyna LA. Tissue Engineered Axon Tracts: The Neuroscientific Basis for Neurorestorative Therapies. Progress in Neurobiology. 2015;125:1-25.

- 8. Koffler J. Biomimetic 3D-Printed Scaffolds for Spinal Cord Injury Repair. Nature Medicine. 2019;25(2):263-269.

- 9. Lu P. Long-Distance Axonal Growth from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells after Spinal Cord Injury. Neuron. 2012;74(4):726-739.

- 10. Bear MF, Connors BW, Paradiso MA. Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain. 4th ed, Wolters Kluwer. 2015.

- 11. Standring S. Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. 41st ed, Elsevier, 2016.

- 12. Watson C. The Spinal Cord: A Comprehensive Review of Anatomy and Function. Neuroscience Research. 2009;63(1):15-27.

- 13. Bartanusz V. The Blood-Spinal Cord Barrier: Morphology and Clinical Implications. Annals of Neurology. 2011;70(2):194-206.

- 14. Fehlings MG. Current and Emerging Therapies for Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. Spine. 2018;43(9):607-613.

- 15. Javed S. Inflammatory Demyelinating Diseases of the Spinal Cord. Journal of Neurology. 2021;268(3):1123-1135.

- 16. Schroeder HW. Primary and Metastatic Spinal Tumors: Diagnosis and Treatment Strategies. Spine Journal. 2019;19(8):1367-1379.

- 17. Nogueira RR. Vascular Disorders Affecting the Spinal Cord: Clinical and Radiological Spectrum. Neuroradiology. 2019;61(9):983-995.

- 18. Yamada K. Etiologies of Spinal Cord Injury: A Comprehensive Review. Neurosurgery Clinics of North America. 2015;26(1):9-20.

- 19. Anderson KD. Targeting Recovery: Priorities of the Spinal Cord-Injured Population. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2004;21(10):1371-1383.

- 20. National SCI Statistical Center (NSC). 2023 Annual Statistical Report for the United States. University of Alabama at Birmingham. 2023.

- 21. McDaid D. The Economic Burden of Spinal Cord Injury in the United States. Spinal Cord. 2019;7(8):635-643.

- 22. Salewski F. Neuromodulation Devices in the Treatment of Spinal Cord Injury. Frontiers in Neurology. 2022;13.

- 23. Shi B. One-Dimensional Nanomaterials for Nerve Tissue Engineering to Repair Spinal Cord Injury. Biomedical Engineering Materials. 2024;3.

- 24. Tetzlaff W. A Systematic Review of Cellular Transplantation Therapies for Spinal Cord Injury. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2011;28(8):1611-1682.

- 25. Badhiwala JH. Global Burden of Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury: Update and Trends. Neuroepidemiology. 2018;50(3-4):174-187.

- 26. Research and Markets. Global Spinal Cord Injury Treatment Market Report 2023-2033. 2023.

- 27. Guan X. Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine Approaches for Spinal Cord Injury. Biomaterials Science. 2023;11(5):1257-1275.

- 28. Serafin A. 3D Printable Electroconductive Gelatin-Hyaluronic Acid Materials Containing Polypyrrole Nanoparticles for Electroactive Tissue Engineering. Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials. 2023;6.

- 29. ClinicalTrials.gov. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Infusion for Chronic Complete Spinal Cord Injury. NCT02510365. 2024.

- 30. Liu S. A Multi-Channel Collagen Scaffold Loaded with Neural Stem Cells for the Repair of Spinal Cord Injury. Neural Regeneration Research. 2021;16(11):2284-2292.

- 31. Zhang T. Multifunctional Aligned RGO-Enhanced GelMA Hydrogel for Spinal Cord Regeneration. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering. 2024.

- 32. Bardy C. Functional Electrical Stimulation to Promote Recovery Following Spinal Cord Injury. Neuroscience Letters. 2015;589:28-36.

- 33. ClinicalTrials.gov. Safety and Feasibility Study of Neuro Regen Scaffold Combined with Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Acute Complete Spinal Cord Injury. NCT03966794. 2023.

- 34. ClinicalTrials.gov. Study of AST-OPC1 in Subacute Cervical Spinal Cord Injury. NCT02326662. 2023.

- 35. ClinicalTrials.gov. Umbilical Cord Blood-Derived Cell Therapy in Spinal Cord Injury. NCT02688049. 2024.

- 36. Tran A. Modulating the Glial Scar for Enhanced Spinal Cord Regeneration. Nature Neuroscience. 2018;21(2):178-188.

- 37. Rosenzweig ES. Restoration of Motor Control via Cortical Stimulation after Spinal Cord Injury. Science. 2018;362(6419):1333-1336.

- 38. Hasanzadeh E. Injectable Hydrogels in Central Nervous System: Unique and Novel Platforms for Promoting Extracellular Matrix Remodeling and Tissue Engineering. Materials Today Bio. 2023;20.

- 39. Chen K. Biomaterial-Based Regenerative Therapeutic Strategies for Spinal Cord Injury. NPG Asia Materials. 2024;16(5):2024.

- 40. Chen Z. NSC-Derived Extracellular Matrix-Modified GelMA Hydrogel Fibrous Scaffolds for SCI Repair. NPG Asia Materials. 2022;14.

- 41. Chen H. 3D Printed Scaffolds Based on Hyaluronic Acid Bioinks for Tissue Engineering: A Review. Biomaterials Research. 2023;27:137.

- 42. Theodore N. Advances in Surgical Management of Spinal Cord Injury. Spine Journal. 2020;20(8):1304-1312.

- 43. Lee Y. An Injectable Bioelectronic Hydrogel for Spatiotemporal Neuromodulation. Science Advances. 2023;9(6):eade8829.

- 44. Li Y. Engineering Spinal Cord Regeneration: Trends, Frontiers and Emerging Strategies. Engineering. 2024;17.

- 45. Tsai EC. Developing Biomaterial Scaffolds for SCI Repair. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2010;219(1-2):1-12.

- 46. Zhang L. NSCs Migration Promoted and Drug Delivered Exosomes-Collagen Scaffold via a Bio-Specific Peptide for One-Step SCI Repair. Advanced Healthcare Materials. 2021;10(4).

- 47. Darrow D, Kumar N, Suresh AK. Epidural Spinal Cord Stimulation Facilitates Immediate Restoration of Dormant Motor and Autonomic Supraspinal Pathways After Chronic Neurologically Complete Spinal Cord Injury. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2019;36(16):1-14.

- 48. Fawcett JW, Asher RA. The Glial Scar and Central Nervous System Repair. Journal of Neuro Engineering and Rehabilitation. 2007;4(1):15.

- 49. Ghosh S. Biomaterial-Based Approaches for Regeneration of Spinal Cord Injury. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2022;145:112449.

- 50. Guo S. Spinal Cord Repair: From Cells and Tissue Engineering to Extracellular Vesicles. Cells. 2021;10(8).

- 51. Qi Z. A Dual-Drug Enhanced Injectable Hydrogel Incorporated with Neural Stem Cells for Combination Therapy in Spinal Cord Injury. Chemical Engineering Journal. 2022;427.

- 52. Qiu C. A 3D-Printed Dual Driving Forces Scaffold with Self-Promoted Cell Absorption for SCI Repair. Advanced Science. 2023;10(23).

- 53. Wang C. 3D-Printed Conductive Scaffolds for SCI Repair. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 2022;16:e 969002.

- 54. Woods I. Biomimetic Scaffolds for Spinal Cord Applications Exhibit Stiffness-Dependent Immunomodulatory and Neurotrophic Characteristics. Advanced Healthcare Materials. 2022;11(1).

- 55. Wu Z. Programmable Conductive Hydrogel with Aligned Microchannels for Spinal Cord Repair. Macromolecular Bioscience. 2024.

- 56. Xia Q. Injectable Self-Healing Conductive Hydrogel Loaded with Nerve Growth Factor for SCI Repair. Bioengineering & Translational Medicine. 2024;9(2):e10448.

- 57. Xue W. Anisotropic Scaffolds for Peripheral Nerve and Spinal Cord Regeneration. Bioactive Materials. 2021;6:4141-4160.

- 58. Xu P. Decellularized Extracellular Matrix-Based Composite Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Regenerative Biomaterials. 2024;11.

- 59. Zhao B. Animal Models for Treating SCI Using Biomaterials-Based Tissue Engineering Strategies. Tissue Engineering Part B: Reviews. 2022;28(1):79-100.

- 60. Zhong Y. Stimuli-Responsive Nanocarriers for Controlled Drug Delivery in Spinal Cord Injury. Journal of Controlled Release. 2015;219:181-192.