Introduction: In the present study, we assessed in a community sample the relationship between the BP propagation velocity, as pulse wave velocity (PWV) and BP parameters (central and brachial).

Methods: 116 non-hypertensive, non-diabetic participants were recruited from the general population. Biodata were acquired using standardized questionnaires. The anthropometries and brachial BP were measured following standard procedures. The central BP was assessed by a validated applanation tonometry using Pulsepen utilizing the principle of generalized transfer function (GTF). Pearson’s correlations coefficient, r was determined between PWV and BP parameters using IBM SPSS package. The P-value was set at ≤.05.

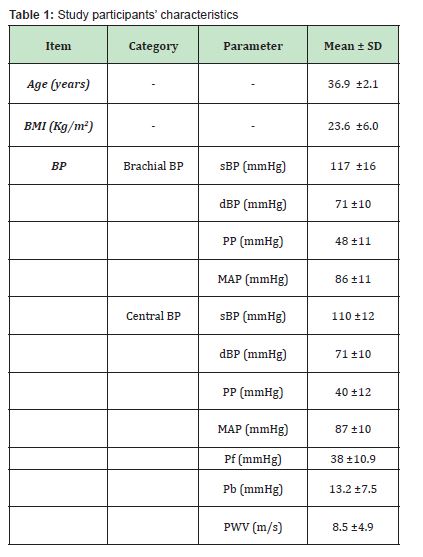

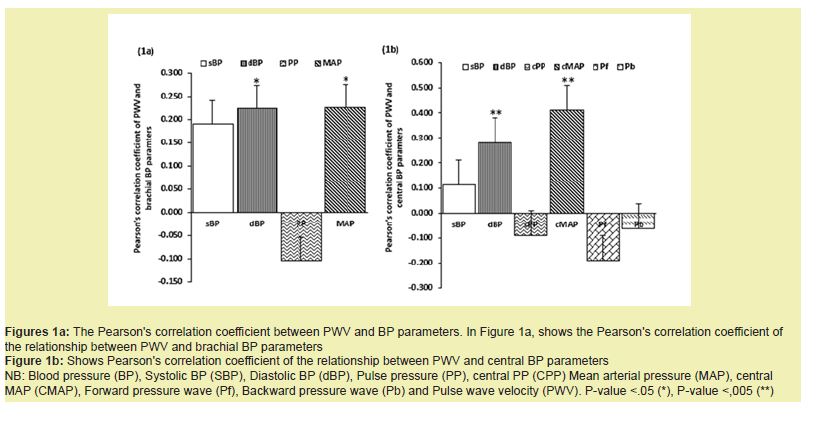

Results: The mean age of the study group was 36.9 ±12.1 years, (18 – 76 years) and mean body mass index (BMI) was 23.6 ±6.0 Kg/m2. The brachial systolic BP and PP were significantly higher than that recorded in central aorta (P <.05). However, both the central and brachial diastolic BP and mean arterial pressure (MAP) were similar (P >.05). And the mean PWV was 8.5 ±4.9m/s. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient, r for PWV vs diastolic BP and MAP were significant (P <.05) but for systolic BP and PP it was not significant (P >.05) and same for forward travelling pressure (Pf) (r =-0.189, p =.048) and backward travelling pressure (Pb) (r =-0.063, p =.511).

Conclusions: Steady state BPs showed better correlation with the PWV. This relationship was irrespective of whether it’s central BP or brachial BP. Indeed, steady state BP ensures better circulation to the target organs, obtained in normal BPs.

Keywords: Systolic blood pressure, Diastolic blood pressure, Target organ damage, Pulse wave velocity, Forward pressure wave, Backward pressure wave

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is an important cause of death globally.1,2 And hypertension is the most important modifiable risk factor for CVD, in western sub-Saharan Africa, where the average life expectancy is abysmally low.3,4 It has been argued recently that blood pressure (BP) value considered as normal (<140/90 mmHg) is arbitrary.5,6 In this regard, BP-associated target organ damage (TOD) may be recorded from systolic BP >115 mmHg.7,8 This therefore suggest looking out for TOD, at BP lower than the generally known hypertensive range. Furthermore, evidences also suggest, that parts of the reasons that target organ changes/damage may not be consistent with BP, is because BP is usually taken at the arm, using the pressure at the brachial artery. However, substantial evidences have shown that brachial BP is a poor surrogate of the pressure that supply the target organs.8-10 Importantly, the central BP, measured at the central aorta reflects better the pressure in the vital organs.11 In practice, the carotid BP is taken as the pressure in the ascending aorta, since the difference between the two is just 1 mmHg. Consequently, central BP parameters are easily assessed using validated, non-invasive, user-friendly gadgets and parameters such as forward pressure, backward pressure and pulse wave velocity have been derived which have been shown to predict cardiovascular out come and able to detect sub-clinical TOD.

Commonly, the target organ changes associated with BP are seen in the hospital setting, when some other complications might have set in. This makes the case management difficult and clinical outcome poorer. To this extent, it has been advocated that cardiovascular target organ changes be sought at the sub-clinical stage, for earlier intervention, to facilitate better outcomes.11-13 In this regard, aortic wall stiffening may occur earlier, way before overt TODs occur. It may therefore be assessed as a surrogate to other target organ changes associated with hypertension. The pulse wave velocity (PWV) is a goal standard for assessment of aortic wall stiffness. However, how much the PWV relates with different BP parameters (brachial or central) in apparently normal population, is not properly understood, and it is the overarching aim of the present study. Moreover, BP is a function of the age,3,14 however, what explains the normalcy of the BP in younger age group is not completely understood, as yet. Therefore, in the present study, we assess in a community sample of adults, with a predominantly younger population, the relationship between the BP propagation velocity, the PWV in both central as well as brachial BP.

The present study was approved by the ethical committees of the Usmanu Danfodiyo University committee for Human research and the Ethical Committee of the Sokoto State Specialist Hospital, with the respective references numbers UDUS/UREC/2020/008 and SHS/SUB/133/Vol 1. Similarly, the participants gave their informed consent before being enrolled in the study and the rules and regulations guiding human research as enshrined in the 1975 Helsinki declaration by the World Medical Association (WMA) were firmly adhered to. 116 non-hypertensive, non-diabetic participants were recruited from the general population in the present study. The biodata of the participants was subsequently acquired, using standardized questionnaires and measuring the anthropometries, in light clothing and bare-footed using a standiometer. The central BP was assessed, after allowing the participant to rest for at least 5 minutes, by a validated applanation tonometry using Pulsepen that utilizes the principle of generalized transfer function (GTF). The brachial BP, was also measured following standard procedures using Omron M1 upper arm BP monitor, alternating 2 different cuff sizes, as appropriate for the participants’ upper am size. The average of 3 readings were used per participant.

For data management, the Preliminary data processing was done using Microsoft excel. Briefly, continuous data were summarized as mean ± SD and differences between central and brachial BP parameters were assessed with student t-test, while chi-square goodness of fit was used to find the difference between dichotomous data, such as proportion of the study population above or below 55 years. However, Pearson’s correlations coefficient, r was determined on the IBM SPSS package, in accordance with the specifications of the vendor. Graphs and tables were also used in the present study, where they make information clearer. The P-value of ≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

The mean age of the study group was 36.9 ±12.1 years, with a range of 18 – 76 years and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 23.6 ±6.0 Kg/m2. In Table 1, the average age of the participants suggests majority of them being of a young population. The BMI and BP also, is conspicuously in the normal range. The brachial systolic BP and PP were significantly higher than that recorded in central aorta (P <.05). However, both the central and brachial diastolic BP and mean arterial pressure (MAP) were similar, essentially being the steady state BPs parameters. Indeed, the central BP parameters including Pf, Pb and the PWV were within the normal range, corroborating the predominantly young and apparently normal study population. Other general characteristic of the participants is as shown in Table 1 below.

In figure 1a below, the Pearson’s correlation coefficient between PWV and brachial BP parameters were depicted. This showed a stronger relationship with both dBP (r =0.224, P =.019), and MAP (r =0.225, P =.025), compared with sBP (r =0.190, P =.047) or PP (r =-0.104, P =.305). Indeed, the relationships were better in the central dBP (r =0.279, P =.003) and cMAP (r =0.410, P =.002), when compared with sBP (r =0.112, P =.245), cPP (r =-0.090, P =.351), Pf (r =-0.189, P =.048) or Pb (r =-0.063, P =.511).

The present data reports that in a general population, comprising mainly of young population, non-diabetics, and non-hypertensive, the systolic BP and PP are significantly higher in the brachial BP, compared to the central BP. Similar to the BP parameters taken in the arm, the central BP parameters were also within the normal range, in this population. Moreover, at this level of normal BP parameters, the diastolic BP and MAP show stronger relationship with PWV, an index of target organ changes, compared to what was observed of the systolic BP, PP or the central wave separation analysis products, including Pf and Pb.

Central BP is the pressure measured in the ascending aorta, but in practice, its measured in the carotid artery, because of the former is just 1 mmHg less. It reflects the better the pressure transmitted to the vital organs like heart, kidneys and the brain better than the pressure in the brachial artery measured at the arm.3,8,15 Further, there is a good body of evidence that the BP recorded from the central arteries are different form that measured in the arm. In this regard, BP in the arm is significantly higher than the pressure recorded in the aorta, owing to the variations to the extent of vascular resistance.

Although, both central and brachial BP are surrogate BPs of the actual BP that runs in the vital organs, the former is a type 2 surrogate BP and therefore a better reflection the BP impact received by the target organs. In this regard, assessment of central BP will facilitate drug specific treatment of arterial hypertension, thereby obviating the inconsistences observed in BP brachial BP compared to central BP on the use of antihypertensive.16 Importantly, in the Conduit Artery Function Evaluation (CAFE) study, it was reported that a combination of antihypertensive (Amlodipine/Lisinopril) medication showed positive effect on central BP without such effect recorded in the brachial BP.17 Based on these evidences, the incorporation of central BP measurement has been advocated, not only in the management of arterial hypertension, but in the prediction of future cardiovascular even and in the drug-specific management. However, there is obviously there is need for more data pool and widespread randomized control trials before convenient clinical application of central BP.

Although, there is substantial evidence that central BP is associated with TOD than BP taken in the arm,12,16 there is no consensus on this, as yet. In this regard, a systematic review12 show that although central BP is not associated with TOD, but it predicts future target cardiovascular outcome than brachial BP could.

Meanwhile, earlier studies2.18-20 mostly on conventional BP assessed relationship between BP and it confounders, where it was shown that steady state BP associate more with confounders compared to the systolic BP or PP in individuals below 50 years of age. And a study by21 where the relationship between both ambulatory day time and night BP and Left ventricular mass index (LVMI) as well as urinary albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR) were evaluated, it was found that diastolic BP showed more association with these indices of target organ changes in day time diastolic BP, similar to BP used in the present study. However, they reported in their study, that systolic night time BP was more associated with the target organ changes.21

Enhanced PWV augments central BP with a consequence on increased reflection in the pressure with untoward consequence on the heart and other target organs.11

However, the study by Jeon, Kim, Lim, Seo, Kim, Zo, Kim22 showed that central pulse pressure (CPP) was more associated with target organ damage among the central BP parameter. However, this study by22 was carried out among elderly and arteriosclerotic patients. Nevertheless, the present data suggests that in young apparently normal people, steady state BP parameters, especially the central components need to be monitored more.

Arterial stiffness is an important early marker of TOD, and blunting it may prevent TOD and consequent cardiovascular event.13 Steady state BPs which includes the diastolic BP and MAP showed better correlation with the PWV, a measure of the propagation velocity of the travelling pressure wave from the aorta to any peripheral point of reference. In the present study, we showed that the relationship between arterial wall stiffness (PWV) with BP was stronger with steady state BP parameters, irrespective of whether it is central BP or brachial BP. These findings corroborate earlier studies,2,18,23 that below the age of 55 years, the steady state BP corresponds with age, anthropometries and other confounders of BP, beyond the dynamic or pulsatile BP parameters. Indeed, steady state BP ensures better circulation to the target organs, that obtains in normal BPs.24,25 We therefore suggest that to determine sub-clinical target organ changes as proposed by guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension, the steady state BP may be a better component to evaluate, but in young individuals.

We are grateful to the Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto (UDUS), which through the Directorate of Research Innovation and Development provided the ideal environment for the study. Similarly, we are indebted to the management of the State Specialist Hospital, Sokoto for providing us some facilities for the study. And finally, the study wouldn’t have been possible without the collaboration of the participants. We appreciate their understanding.

This Research Article received no external funding.

Regarding the publication of this article, the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- 1. Chen J, Aronowitz P. Congestive Heart Failure. The Medical clinics of North America. 2022;106(3):447-458.

- 2. Spitaleri G, Zamora E, Cediel G, et al. Cause of Death in Heart Failure Based on Etiology: Long-Term Cohort Study of All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality. Journal of clinical medicine. 2022;11(3).

- 3. McEniery CM, Cockcroft JR, Roman MJ, et al. Central blood pressure: current evidence and clinical importance. European heart journal. 2014;35(26):1719-1725.

- 4. Sani M, Beth A Davison, Gad Cotter, et al. Renal dysfunction in African patients with acute heart failure. European journal of heart failure. 2014.

- 5. Kjeldsen SE. Hypertension and cardiovascular risk: General aspects. Pharmacological research. 2018;129:95-99.

- 6. O'Brien E, Asmar R, Beilin L, et al. European Society of Hypertension recommendations for conventional, ambulatory and home blood pressure measurement. Journal of hypertension. 2003;21(5):821-848.

- 7. Committee G. 2003 European Society of Hypertension-European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Journal of hypertension. 2003;21(6):1011-1053.

- 8. Cheng HM, Chuang SY, Sung SH, et al. 2019 Consensus of the Taiwan Hypertension Society and Taiwan Society of Cardiology on the Clinical Application of Central Blood Pressure in the Management of Hypertension. Acta Cardiologica Sinica. 2019;35(3):234-243.

- 9. Cheng HM, Chuang SY, Wang TD, et al. Central blood pressure for the management of hypertension: Is it a practical clinical tool in current practice? Journal of clinical hypertension (Greenwich, Conn). 2020;22(3):391-406.

- 10. Veen PHvd, Geerlings MI, Visseren FLJ, et al. Hypertensive Target Organ Damage and Longitudinal Changes in Brain Structure and Function. Hypertension (Dallas,Tex:1979). 2015;66(6):1152-1158.

- 11. Hashimoto J. Central hemodynamics and target organ damage in hypertension. The Tohoku journal of experimental medicine. 2014;233(1):1-8.

- 12. Kollias A, Lagou S, Zeniodi ME, et al. Association of Central Versus Brachial Blood Pressure With Target‒Organ Damage: Systematic Review and Meta‒Analysis. Hypertension (Dallas,Tex:1979). 2016;67(1):183-190.

- 13. Vasan RS, Short MI, Niiranen TJ, et al. Interrelations Between Arterial Stiffness, Target Organ Damage, and Cardiovascular Disease Outcomes. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2019;8(14):e012141.

- 14. Chrysant S, Chrysant G. The Age-Related Hemodynamic Changes of Blood Pressure and Their Impact on the Incidence of Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke: New Evidence. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension 2014;6(2).

- 15. Cheng HM, Chuang SY, Wang TD, et al. Central blood pressure for the management of hypertension: Is it a practical clinical tool in current practice?. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2020;22(3):391-406.

- 16. Agabiti Rosei E, Mancia G, O’Rourke MF, et al. Central Blood Pressure Measurements and Antihypertensive Therapy. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex : 1979). 2007;50(1):154-160.

- 17. Williams B, Lacy PS, Thom SM, et al. Differential impact of blood pressure‒lowering drugs on central aortic pressure and clinical outcomes: principal results of the Conduit Artery Function Evaluation (CAFE) study. Circulation. 2006;113(9):1213-1225.

- 18. Bamaiyi A, Madaki H, Musa H, et al. Systolic pressure, not the diastolic pressure expresses better the relationship between age and blood pressure changes in a community sample of adults. Niger J Basic Clin Sci. 2023;20:34-39.

- 19. Benetos A, Petrovic M, Strandberg T. Hypertension management in older and frail older patients. Circ Res. 2019;124:1045‑1060.

- 20. Shen W, Zhang T, Li S, et al. Race and sex differences of long‑term blood pressure profiles from childhood and adult hypertension: The Bogalusa heart study. Hypertension Research. 2017;70:66‑74.

- 21. Veerman DP, de Blok K, van Montfrans A. Relationship of steady state and ambulatory blood pressure variability to left ventricular mass and urinary albumin excretion in essential hypertension. American journal of hypertension. 1996;9(5):455-460.

- 22. Jeon KH, Kim HL, Lim WH, et al. Associations between measurements of central blood pressure and target organ damage in high‒risk patients. Clinical Hypertension. 2021;27(1):23.

- 23. Benetos A, Petrovic M, Strandberg T. Hypertension management in older and frail older patients. Circ Res. 2019;124:1045-1060.

- 24. Salvi P. Pulse Waves: How Vascular Hemodynamics Affects Blood Pressure. 2nd (edn.) Switzerland: Springer; 2017.

- 25. Mitchell GF, Gudnason V, Launer LJ, et al. Hemodynamics of Increased Pulse Pressure in Older Women in the Community‒Based Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility–Reykjavik Study. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex : 1979). 2008;51(4):1123-1128.