This paper presents a comprehensive review of numerical modelling techniques for filtering oil droplets from produced water, a critical challenge in the oil and gas industry. The study analyzes current research, highlighting the role of numerical models in improving filtration efficiency and mitigating environmental impacts. Our methodology involves a systematic literature review of theoretical frameworks and computational approaches, including Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), multiphase flow dynamics, and machine learning. Key findings demonstrate that numerical models are vital for predicting filtration performance and understanding oil-water interaction dynamics. However, limitations remain in their predictive accuracy across diverse operational conditions, underscoring the need for experimental validation. The review also identifies emerging trends that advance the understanding of filtration processes. Furthermore, the study employs artificial intelligence to explore predictive analytics for emulsion flooding optimization. The simulation results from an initial model are compared against three global optimization algorithms: Differential Evolution (DE), Differential Evolution with Crossover Enhancement (DECE), and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO). For fitting the coreflooding model, both DE and DECE demonstrated a superior and excellent fit with coefficient of determination (R²) value of 0.9914. PSO, while yielding the highest oil recovery, showed a slightly lower accuracy (R² = 0.9818) due to early-to-mid injection stages. Enhanced numerical modelling can lead to more efficient filtration systems, promoting sustainable practices. These advancements facilitate effective oil-water separation, ensuring environmental compliance and reducing the ecological footprint of oil production.

Keywords: Numerical modelling, Filtration techniques, Produced water management, Oil water emulsions, Computational fluid dynamics

Produced water management is an essential component of the oil and gas sector, since it encompasses the process of treating and disposing of water that is extracted together with hydrocarbons during production. A key setback in the management of generated water is the presence of oil-water emulsions, which are enduring combinations of oil droplets scattered in water. These emulsions provide notable environmental and operational difficulties since they are able to contaminate water bodies as well as impede the reinjection process. Efficient separation of oil droplets from generated water is crucial for complying with environmental standards and ensuring the long-term viability of oil and gas operations. The necessity for effective filtering methods is emphasized by the rising quantity of generated water and the strict discharge criteria enforced by regulatory authorities.

This article provides a thorough examination of the numerical modelling and simulation methods adopted in the filtering of oil droplets from generated water. Numerical modelling is a potent tool for comprehending and forecasting the behaviour of intricate filtration processes, providing valuable insights that are sometimes hard to get just through experimental approaches. The study will encompass a range of theoretical frameworks and computational methodologies that have been devised to simulate the process of oil droplet filtering. The research will showcase current progress in modeling methodologies, specifically focusing on the incorporation of multiphase flow dynamics, computational fluid dynamics (CFD), and machine learning algorithms. The study attempts to comprehensively analyze these developments to gain a thorough grasp of the present state of research in this topic and to pinpoint prospective areas for future exploration.

The numerical simulation of oil droplet filtration from generated water is an important combination of theoretical and computational methods in the fields of environmental engineering and fluid dynamics. With the increasing need for efficient water treatment methods, especially in the oil and gas industry, there has been a notable focus on understanding and simulating the intricate processes involved in filtration. Recent research has revealed progress in modeling tools, which enhance our comprehension of the fundamental principles that regulate filtration and also enhance the operational efficiency of these processes. Researchers are using a combination of different theoretical frameworks and advanced computational tools to develop new and creative ways for reducing the environmental effects of produced water. This will help promote sustainable practices in the oil and gas sectors.

This introduction establishes the context for an investigation of the present condition of research in this field, highlighting the significance of ongoing progress in numerical modelling to tackle the difficulties presented by oil droplet filtering.

Produced oil-water emulsions: Formation and Characteristics

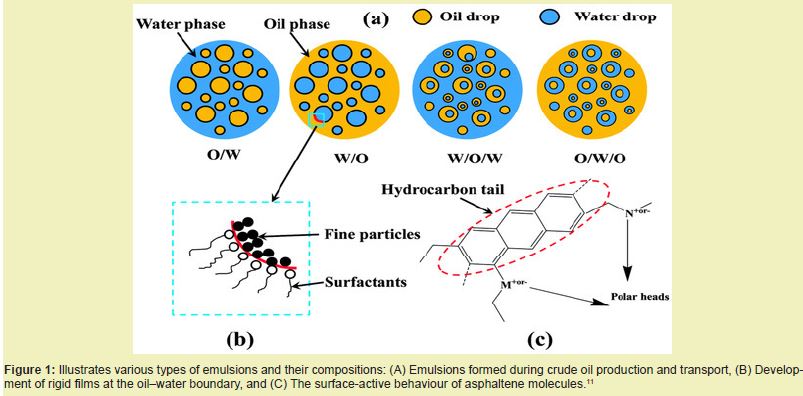

When oil and water interact under various conditions throughout the oil production process, oil-water emulsions occur. Mechanical equipment, such as pumps and valves, creates shear forces that disperse oil droplets in water, resulting in emulsion formation.1 Chemical additives, such as surfactants and demulsifiers, can stabilize or destabilize emulsions depending on their characteristics and concentration.1 In addition, the water content of the produced fluid has a significant influence on the chances of emulsion formation.2 Oil-water emulsion creation, stabilization, and separation are key processes in a variety of sectors, including petroleum production, food processing, and pharmaceutical manufacturing.4 Emulsifiers, such as proteins, phospholipids, or nanoparticles, are essential for stabilizing these emulsions. The presence of interracially active materials, such as fine particles, also contributes to the stability of emulsions. Understanding these factors is essential for optimizing production processes and mitigating potential issues related to emulsion formation.

The behaviour and stability of oil-water mixtures are significantly influenced by their physical and chemical properties. Key characteristics include droplet size distribution, viscosity, and overall stability. The stability and separation efficiency of an emulsion are affected by droplet size distribution, with smaller droplets often leading to more stable emulsions. The viscosity of an emulsion is influenced by the oil-to-water ratio and the presence of emulsifying agents, which in turn affect how easily the emulsion can be handled and processed. Several factors, including interfacial tension, the presence of stabilizing chemicals, and the system’s temperature and pressure conditions, influence the stability of the system.5 Separating oil and water mixtures poses considerable difficulties, especially when considering reinjection methods. The stability of emulsions is impacted by the presence of stabilizing chemicals and the droplet size, this in turn reduces the effectiveness of standard separation procedures. Additionally, the use of advanced separation techniques and equipment, like high-pressure homogenizers and ultrasonic emulsification, can further enhance the stability and separation efficiency of oil-water mixtures.6,7

High viscosity and small droplet sizes make filtering challenging. To achieve effective separation, advanced technologies are required.3 This challenge has led to the development of specialized filtration systems.1 As a result, there is a growing need for innovative numerical modelling tools to improve filtering efficiency and better manage produced water.

The gravity separation process is the most commonly used method for emulsion separation.8 In this process, components of the well stream such as oil and water separate due to their different densities. When the mixture remains undisturbed for a sufficient period, the specific gravity differences cause the fluids to settle into distinct layers. The use of chemical additives however, can interfere with this separation, making filtration more complex.

Categorization of emulsions

Emulsions may be categorized in several ways depending on different criteria.9 According to Kokal, the three primary types include water-in-oil (W/O), oil-in-water (O/W), and multiple emulsions.10 Multiple emulsions, also known as complex emulsions, consist of soft materials formed by dispersed droplets that contain even smaller droplets within them. Common examples of double emulsions are oil-in-water-in-oil (O/W/O) and water-in-oil-in-water (W/O/W). Their specific compositions are illustrated in Figure 1.

The impact of oil–water emulsions

The effective management of waste oil–water emulsions remain a critical environmental concern due to their substantial ecological and health-related impacts.12 In 2013, global volumes of oily wastewater were estimated to range between 10 and 15 billion cubic meters, with a notable upward trajectory observed in recent years.13 A comprehensive review by Chen covering research from 1998 to 2021, revealed a consistent increase in the number of published studies, culminating in a peak in 2021 with an annual growth rate of 9.55%.14 This trend underscores the growing significance and anticipated future development of this field.15

Industrial oil–water emulsions pose serious risks to both human health and the environment, primarily due to their high concentrations of heavy metals. Heavy metals such as thallium have been linked to hair loss in humans,16 while elevated exposure to antimony and chromium (Sb and Cr) has been associated with increased cancer risk.17,18 Lead toxicity can lead to cognitive impairments in children and various heavy metals are known to adversely affect vital organs including the kidneys, heart, nervous system, and skin. Notable examples include Minamata disease caused by mercury poisoning and Itai-Itai disease resulting from cadmium exposure.19

Although certain essential heavy metals play a role in regulating biological functions,20 it is imperative to ensure that waste oil–water emulsions are properly treated before being discharged into densely populated areas. Heavy metals, unlike many pollutants, are typically non-biodegradable and contribute significantly to environmental contamination. When wastewater is released without proper treatment, heavy metals tend to bind with organic and inorganic colloids and particles, eventually accumulating and settling at the bottom of water bodies. Toxic metals such as lead, thallium, cadmium, arsenic, and antimony pose serious environmental risks. For instance, mercury transforms into methylmercury in aquatic environments, forming highly toxic sediments.21 Cadmium contamination disrupts plant growth and metabolic functions, entering ecosystems through industrial discharge, absorption, and surface runoff into soils and sediments.22 Additionally, substantial quantities of zinc from mineral processing can negatively impact both ecosystems and living organisms.23

The roles of emulsifiers

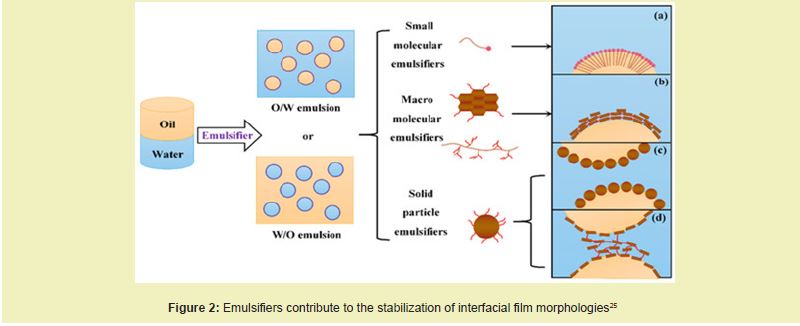

Emulsifiers play a crucial role in maintaining the long-term stability of oil–water emulsions. They achieve this by forming a resilient film at the oil–water interface, which lowers the interfacial tension (IFT) and inhibits the merging of droplets. Emulsifiers are typically categorized into three types: small molecule emulsifiers, macromolecular emulsifiers, and solid particles. These classifications are illustrated in Figure 2, which depicts the contribution of these different emulsifier types to stabilizing interfacial film morphologies.24,25

Filtration techniques for oil-water emulsions

Traditional methods for filtering oil–water emulsions primarily rely on mechanical and chemical techniques. The mechanical coalescence process involves the fusion of tiny oil droplets into larger ones, which can be more easily separated from water. This method typically utilizes coalescing filters or media to facilitate droplet aggregation.1

Another common approach is gravity separation, which leverages the density difference between oil and water. In this method, the emulsion is placed in a tank where gravity causes the denser water to settle, allowing the lighter oil to rise. While this technique is cost-effective and straightforward, it may be ineffective for stable emulsions containing very small droplets.26

Chemical demulsifiers offer an alternative solution by breaking down the molecular film surrounding oil droplets, promoting their coalescence and separation from water. These agents are selected based on the specific characteristics of the emulsion and can significantly enhance the efficiency of the separation process.2

Recent advances in filtering technology have brought novel approaches for increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of oil-water separation. One such technology is membrane filtration, which uses semi-permeable membranes to separate oil droplets from water. These membranes, with precise hole diameters, allow water to pass through while trapping oil droplets. This approach not only ensures a high level of separation, but it can also be adapted to different emulsion qualities.27 Under ideal conditions, membrane filtration can achieve separation efficiencies of more than 99%, according to research.28 Furthermore, the diversity of membrane materials, such as polymeric and ceramic membranes, permits customization based on the individual requirements of the separation process.29 Moreover, advancements in membrane surface modification techniques have further enhanced the anti-fouling properties and longevity of these membranes, making them more sustainable and cost-effective in the long run.30,31

Nanotechnology has considerably advanced filtering processes, especially with the use of nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes and graphene. These materials are used to generate superior filtering media that have improved surface characteristics and high adsorption capabilities. The incorporation of nanoparticles into filtration systems has resulted in significant advancements in water purification. Carbon nanotubes, for example, have a huge surface area and unique electrical characteristics that help them absorb pollutants.32 Similarly, graphene-based filters have outstanding mechanical strength and chemical stability, making them appropriate for long-term usage in diverse filtration applications.33 Moreover, the high efficiency of these nanomaterial-based filters in removing oil and other pollutants from water has been well-documented. Studies have shown that these filters can achieve removal efficiencies of over 99% for certain contaminants.15 This makes them highly effective for use in industries where water contamination is a significant concern, such as in oil spill clean-ups and wastewater treatment.34

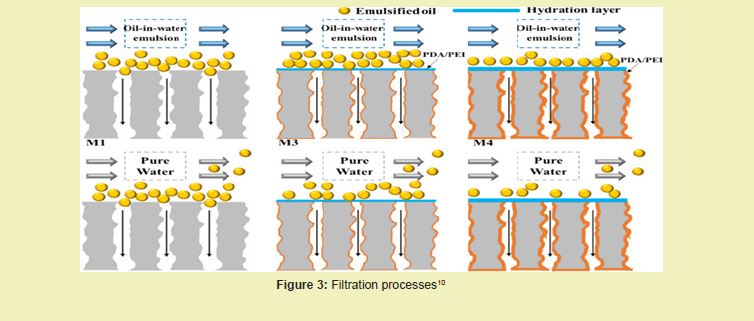

Figure 3, shows that advanced filtration materials include superhydrophobic compounds, which reject water while selectively attracting oil. These materials can be utilized to create filters and coatings that improve the separation process. For example, superhydrophobic filters may efficiently separate oil and water, making them useful in environmental cleanup efforts.24 In addition, the advancement of responsive materials - those that alter their properties when exposed to external factors like pH or temperature - has introduced promising possibilities for creating dynamic and highly efficient filtration systems.31 These smart materials can adapt to changing environments, increasing filtration performance and adaptability.

Numerical modelling of filtration processes

Numerical modelling approaches are vital tools for comprehending and enhancing filtering processes. Three often employed approaches are Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), Discrete Element Method (DEM), and Finite Element Method (FEM). Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) is an effective method employed to model and analyze the movement of fluids and the transfer of heat. The process entails solving the Navier-Stokes equations to forecast the behaviour of fluids under different circumstances. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) is highly advantageous in simulating the intricate interplay between oil droplets and water during filtration operations. It enables a meticulous examination of flow patterns and separation effectiveness.35 The DEM is employed to simulate the behaviour of systems composed of discrete particles. Within the realm of filtration, the DEM can replicate the motion and interplay of oil droplets within a permeable substance. This technique facilitates the comprehension of the process by which droplets combine, separate, and are trapped by the filter material.36

The Finite FEM is a popular computational technique for solving complicated engineering and mathematical physics issues. It is especially useful for simulating the structural response of filter media under varying loading situations. FEM can provide researchers with useful insights into the mechanical stability and deformation behaviour of filters during operation.37 This combination technique improves simulation accuracy, resulting in greater prediction of filter performance. Additional research has proved the usefulness of FEM in many applications, such as fluid-structure interaction38 and thermal analysis,39 which further supports its utility in engineering simulations.

Simulating the flow of emulsions through porous materials poses unique difficulties due to the intricate behaviour of multiphase flow. This phenomenon involves the concurrent movement of oil droplets and water within the porous structure of the filtering medium. Effectively addressing these complexities requires solving a set of interrelated equations for each phase, while also accounting for the interactions between the fluid phases and the porous material itself.40,41

Pore-scale modeling focuses on accurately representing the intricate pore structure within the filter medium. This approach allows for the replication of fluid flow at a microscopic scale, providing valuable insights into how pore structure affects the movement and entrapment of oil droplets.41 Additionally, the properties of emulsions, like the droplet size distribution, viscosity, and interfacial tension, significantly influence their movement through porous materials and their separation efficiency. Numerical models must consider these factors to accurately predict filtration performance.26 The versatility of emulsion templating extends beyond porous polymers, encompassing various materials and applications, highlighting the importance of understanding emulsion behaviour in porous media.24

Simulations are critical in calculating filtration efficiency, improving filter design, and assessing the efficacy of various filtering techniques. To predict filtration performance, numerical modelling techniques are employed to estimate the percentage of oil droplets removed from the emulsion as it passes through the filtering medium. This necessitates extensive simulations of the flow and capture mechanisms, taking into account the parameters of both the emulsion and the filter media.27 Filter design optimization entails running simulations to investigate various filter designs and medium materials. Researchers can determine the most efficient solutions for specific applications by comparing the performance of different designs.24

Evaluating the performance of various filtering systems entails comparing computer simulation findings to real-world experimental data. Such comparisons are essential for validating numerical models and ensuring they accurately represent the real-world behaviour of filtration processes. For instance, Smith demonstrated that incorporating the microstructure of filter media into simulations significantly enhanced their precision.33

Multiple studies demonstrate a gap in accurately predicting filtration performance under diverse, real-world conditions. For example, the study by del Carmen Mendez showed discrepancies between theoretical models and experimental observations, highlighting the need for improved numerical techniques.42 The Hwang and Sharma study, while effective, notes its limitations in investigating various crude oil types. The summarized findings consistently show that key variables like droplet size, concentration, flow velocity, and physicochemical conditions (pH and ionic strength) have a significant impact on filtration efficiency and permeability.43 The study by Moghadasi specifically found that particle concentration has a more substantial effect on reducing permeability than the flow rate.44

Table 1 emphasizes the necessity of validating numerical models with experimental data to ensure their reliability and applicability to real-world scenarios. Studies by Iliev and Laptev and Zarin both validated their numerical models with strong agreement to experimental results. The reviewed papers often focus on specific filtration mechanisms, such as straining, interception, droplet retention, and the role of emulsifiers, which indicates a highly specialized and fragmented approach to a complex problem.45-46

This synthesis of information from Table 1 and the paper's summary confirms that while numerical modelling has advanced significantly, the primary challenge remains the development of robust, predictive models that can reliably perform across a wide range of real-world variables and complex fluid interactions.

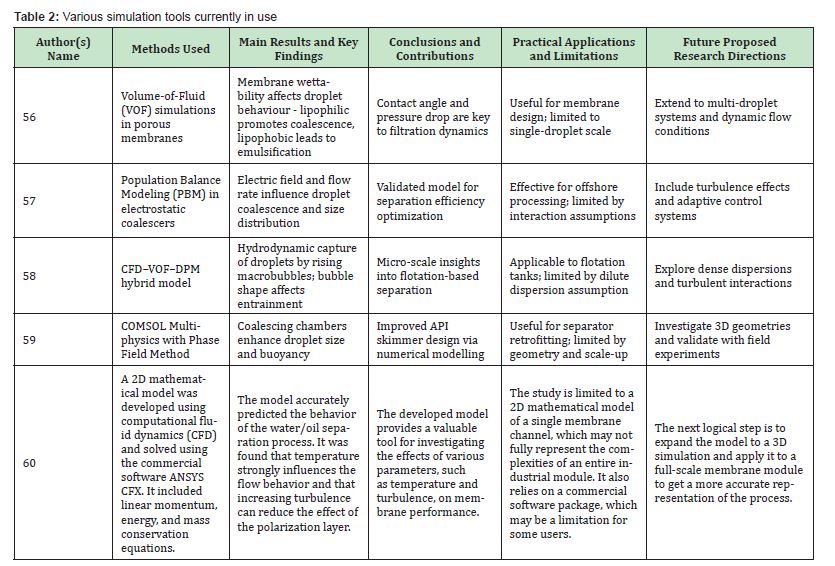

Based on a synthesis of recent studies and simulation tools used in oil droplet filtration from produced water, Table 2 presents a comprehensive list of key articles with inferences and deductions relevant to the study. The studies employ a range of numerical methods - VOF, PBM, CFD-DPM, FDM, and COMSOL - highlighting the need for a comparative framework in your review. Design Implications: Most findings emphasize the role of geometry, flow conditions, and material properties, which aligns with your goal of optimizing filtration systems. Gaps identified include limited multi-scale modeling (micro to macro), Few studies integrate real-time control or AI-enhanced simulations, Sparse validation with field data. These gaps present opportunities for your study to propose hybrid simulation frameworks, AI-assisted optimization, and multi-scale validation protocols.

This section presents and compares the simulation outcomes from the baseline emulsion model with the optimized results obtained using three global optimization algorithms available in CMOST: Differential Evolution (DE), Differential Evolution with Crossover Enhancement (DECE), and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO). The comparison highlights the extent to which each algorithm improves the model’s predictive accuracy and alignment with experimental data. The objective was to improve the match to experimental data and evaluate the effect of emulsion parameters on cumulative oil recovery. In emulsion modelling, optimizers help improve accuracy by automatically adjusting model parameters (such as droplet size distribution coefficients, interfacial tension factors, or viscosity constants) to minimize the difference between predicted and experimental results. Optimizer finds the best-fitting values without manual trial-and-error and ensuring the model reflects underlying physical behaviour rather than fitting errors. The data used were experimental work done by Iryna.61

Reservoir model

The core-scale model used in this study is a 20 × 1 × 1 Cartesian grid representing a homogeneous rock sample. One injector and one producer were placed at opposite ends to simulate linear core flooding. The emulsion flooding mechanism was implemented using the approach described by Iryna61 Figure 4.

Initial model performance

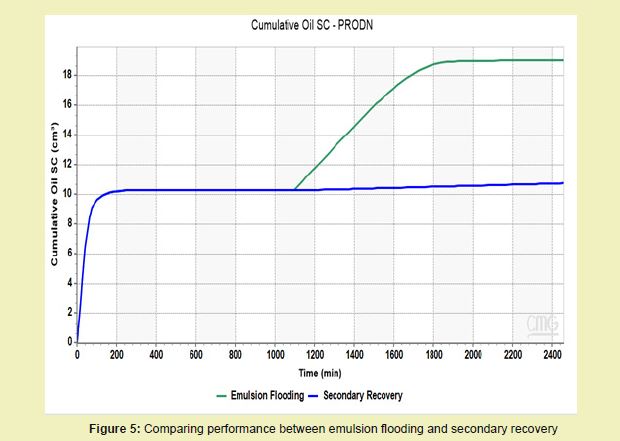

The initial base model simulated a basic waterflood and achieved a cumulative oil recovery of 10.7646 cm³. After implementing emulsion flooding for Enhanced Oil Recovery: Filtration Model and Numerical Simulation by Iryna61 the cumulative oil increased to 19.0121 cm³. While it captured the general trend of the recovery

Initial model performance

In Figure 5, the initial base model simulated a basic waterflood and achieved a cumulative oil recovery of 10.7646 cm³. After implementing the emulsion flooding model based on Emulsion Flooding for Enhanced Oil Recovery: Filtration Model and Numerical Simulation by Iryna,61 the cumulative oil increased to 19.0121 cm³. While it captured the general trend of the recovery curve, major deviations were observed in the transition region between water breakthrough and plateau.

Flooding optimization

Each optimization algorithm adjusted key parameters affecting emulsion behaviour and relative permeability to improve history matching. The optimized parameters include the following ones.

Each optimization algorithm adjusted a set of critical parameters related to emulsion behaviour and fluid flow to improve the match with experimental cumulative oil data. The parameters optimized included:

- a. FREQFAC – Filtration coefficient governing emulsion particle capture

- b. PERMSCALE – Permeability scaling factor that controls capture behaviour

- c. SOLIDMIN – Minimum entrapped solid concentration affecting flow restriction

- d. KRS Parameters – Governing relative permeability characteristics:

- i. Krgcl – Gas relative permeability at connate liquid

- ii. SORW – Residual oil saturation in the water-oil system

- iii. KROCW – Oil relative permeability at connate water

- iv. KRWIRO – Water relative permeability at irreducible oil

- v. SOIRW – Irreducible oil saturation (water-oil)

- vi. SWCON – Connate water saturation

- vii. SWCRIT – Critical water saturation

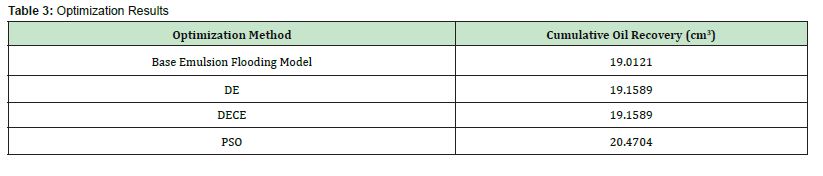

Cumulative oil recovery

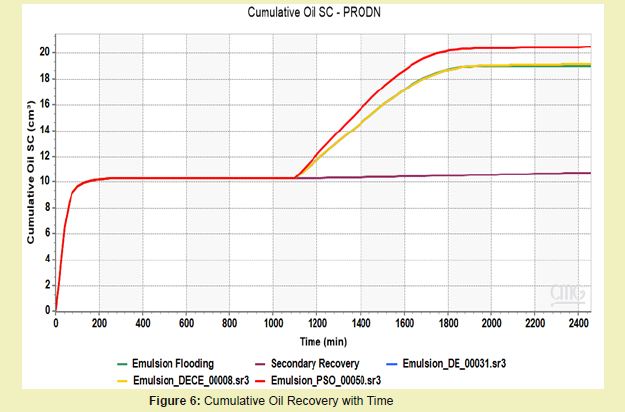

The optimization results are summarized in table 3. Table 3 shows the various optimization methods used in the flood optimization and their respective cumulative oil recovery. While DE and DECE provided modest improvements in matching the experimental transition region, PSO produced the highest recovery, reaching 20.4704 cm³ as shown in Figure 6. This suggests PSO explored more aggressive combinations of permeability and saturation inputs, potentially altering the shape and end-point of the curve more substantially than DE/DECE optimizers.

Water cut

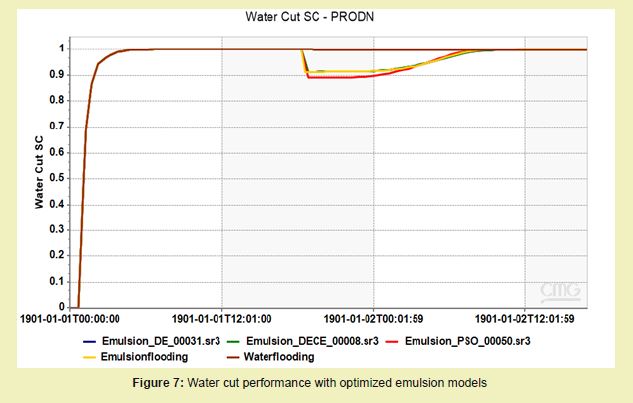

The water cut profile for the base waterflooding case shows early water breakthrough and rapid rise to nearly 100%, indicating poor sweep efficiency. After implementing emulsion flooding (orange line), the water cut is significantly suppressed, especially in the early-to-mid production phase.

As indicated in Figure 7, optimized models (DE, DECE, and PSO) all achieved reduced water cut levels. Notably, DECE and DE held the water cut below 90% longer than the base emulsion flooding case, while PSO demonstrated a delayed rise, indicating stronger water flow resistance due to emulsion capture and diversion.

Pressure optimization

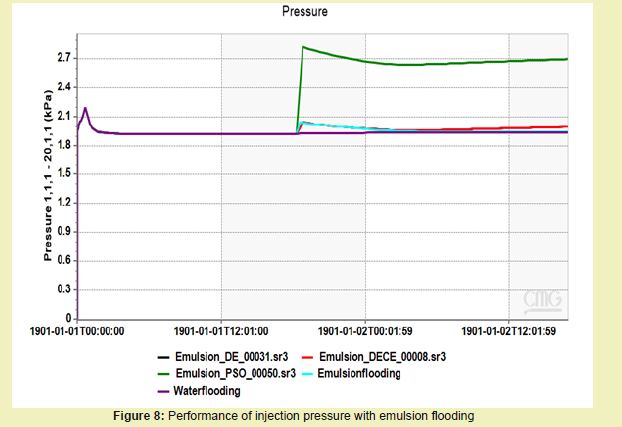

In terms of injection pressure, the base waterflood maintained a relatively flat and low-pressure profile. When emulsion flooding was applied, pressures increased slightly, as expected due to flow restriction effects from trapped emulsions, as shown in Figure 8.

The PSO case showed a sharp increase in pressure early on, followed by a sustained hold of pressure around 2.6520 kPa. This behaviour indicates more aggressive trapping and flow diversion, possibly pushing the limits of realistic injectivity. DE and DECE maintained stable, moderate pressure responses, suggesting more controlled entrapment.

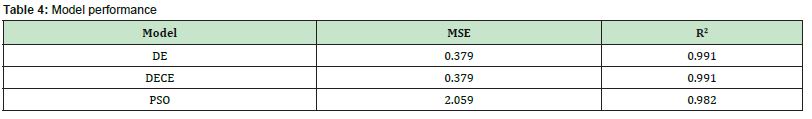

Statistical evaluation

To evaluate model performance, Mean Squared Error (MSE) and R² were calculated against the reference cumulative oil data. DE and DECE both showed excellent fits (R² = 0.9914), while PSO, despite having the highest oil recovery, showed slightly lower accuracy (R² = 0.9818) due to curve deviation in early-to-mid injection Table 4.

Optimized results

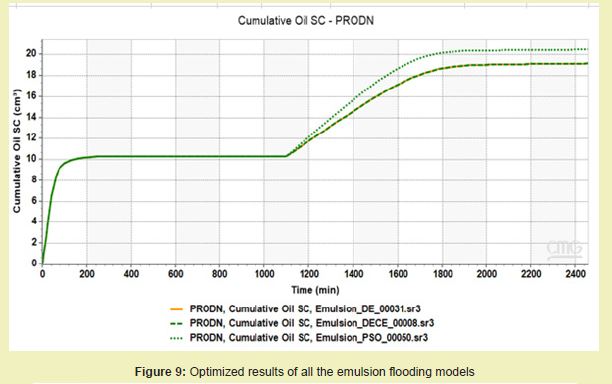

In Figure 9, it can be seen that among the three cases, the Emulsion_PSO_00050.sr3 (dotted line) yields the highest cumulative oil recovery, reaching slightly above 20 cm³. This suggests that the PSO (likely referring to Particle Swarm Optimization) case is the most effective in enhancing oil production in this scenario. Emulsion_DECE_00008.sr3 performs next best, with a final recovery close to 19 cm³. Emulsion_DE_00031.sr3 lags slightly behind, ending with a cumulative oil volume just under 19 cm³.

The optimized results indicate that the PSO-optimized emulsion strategy led to the maximum oil recovery, outperforming the DE and DECE approaches. This suggests that PSO is a more effective optimization method for enhancing cumulative oil production under the given reservoir and operational conditions. Future designs or simulation studies should consider PSO or hybrid strategies for optimal results in Figure 9.

Verifying the precision of numerical models poses a substantial difficulty in filtering procedures. Numerical models frequently depend on simplifications and assumptions that may not comprehensively encompass the intricacies of real-world systems. This might result in disparities between the forecasts made by the model and the actual outcomes. Experimental validation is essential for confirming the correctness of these models. Acquiring accurate experimental data might pose challenges and incur high costs, especially for extensive applications35. Furthermore, the validation procedure is made more complex by the limits of existing modelling tools, which are unable to adequately reflect all physical processes associated with filtering.40

Simulating intricate filtering processes has significant computational requirements, which is a key constraint. Computational resources of considerable magnitude are necessary for numerical models, particularly those that involve multiphase flow dynamics and intricate pore-scale representations. High-resolution simulations are characterized by their time-consuming nature and high computing costs, rendering them unsuitable for regular utilization in large-scale applications.41 The progress in processing power and algorithms is assisting in reducing these difficulties, but the requirement for effective and scalable modeling methodologies remains crucial.37

Uncertainty quantification and sensitivity analysis are crucial elements of the numerical modelling process. Uncertainties can originate from several sources, such as model parameters, boundary conditions, and the intrinsic unpredictability of the system being simulated. It is crucial to quantify these uncertainties to comprehend the dependability and resilience of model predictions.27 Sensitivity analysis is a technique used to discover the factors that have the greatest influence on model outputs and evaluate the extent of their impact. The provided information is crucial for enhancing the precision of the model and directing experimental endeavors to minimize uncertainties.26

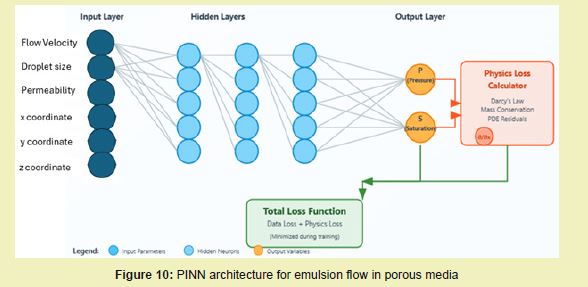

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) with traditional numerical methods is poised to revolutionize the modeling and simulation of emulsion filtration. While conventional ML models excel at identifying patterns in data, a particularly promising frontier is the development of Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs). PINNs represent a paradigm shift by embedding the fundamental physical laws - such as the Navier-Stokes equations for fluid dynamics, conservation of mass, and Darcy's law for flow in porous media - directly into the architecture and loss function of the neural network.62 This hybrid approach ensures that predictions are not only data-driven but also adhere to known physical principles, greatly enhancing their predictive accuracy and generalizability, especially in data-sparse regimes common in complex multiphase flow scenarios.

The AI-driven optimization work presented in this study serves as a critical foundation for this next step. Our use of Differential Evolution (DE), DECE, and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) successfully demonstrated the power of global algorithms in tuning model parameters (e.g., FREQFAC, PERMSCALE, and KRS parameters) to achieve an excellent history match. PINNs can build upon this by moving beyond parameter tuning to learning the entire underlying physics of the filtration process. For instance, a PINN could be trained on the experimental core-flooding data and simulation results generated in this study, with the governing equations acting as a constraint. This would create a surrogate model capable of making ultra-fast and physically consistent predictions of oil recovery and water cut under new, unseen operational conditions, effectively bridging the gap between high-fidelity numerical simulations and rapid engineering design Figure 10.

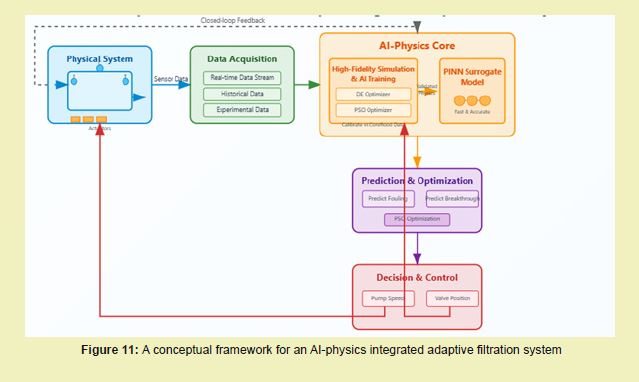

The synergy between numerical models and real-time monitoring systems will be further amplified by these AI advancements. The envisioned future involves adaptive, self-optimizing filtration management systems. Real-time sensor data on produced water quality (e.g., oil-in-water content, pressure differential) would feed into a digital twin powered by a PINN-based surrogate model. This system would not only forecast system performance but also proactively recommend or autonomously implement adjustments to filtration parameters (e.g., flow rates, backwash cycles, chemical dosing), ensuring optimal efficiency and compliance under dynamic conditions.

Ultimately, these advanced modeling capabilities are indispensable for promoting sustainability. By providing unprecedented accuracy in predicting the long-term behaviour of filtration systems, PINNs and integrated AI frameworks enable the design of more efficient and environmentally friendly processes. This includes minimizing energy consumption, reducing chemical usage, and ensuring that reinjection practices have a minimal ecological footprint, thereby aligning operational goals with critical environmental stewardship responsibilities Figure 11.

Dataset Preparation and Annotation

The dataset for this study was generated using experimental model saturation profiles (oil and water) optimized by Iryna61. The images were categorised into two distinct classes: 'oil saturation' and 'water saturation'.

The annotation process was conducted using Roboflow, an online platform for computer vision projects. Each image was annotated with pixel-level precision using a semantic segmentation approach. This method involved outlining the regions corresponding to each saturation class, thereby creating detailed masks that label every pixel as either 'oil sat.' or 'water sat.'. Upon completion of the annotation, the dataset was exported in the Common Objects in Context (COCO) segmentation format, which includes JSON files containing the annotation metadata alongside the images. To increase the dataset size and improve model robustness, data augmentation techniques were applied, resulting in a dataset of 625 images.

The final dataset of 625 images was randomly split into a training set (approximately 60%), a validation set (approximately 20%), and a testing set (approximately 20%). This resulted in a training set used for model learning and a test set reserved for evaluating the model's final performance.

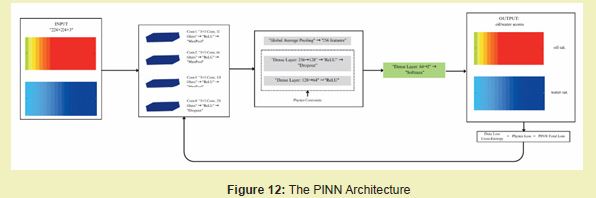

Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN) Architecture

A custom Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN) was designed for the binary classification of saturation profiles. The model architecture, illustrated in Figure 12, integrates convolutional layers as a backbone with a physics-informed loss component to guide the learning process.

The convolutional layers, as a backbone, serve as a feature extractor and consist of four sequential convolutional blocks. Each block includes a 2D convolutional layer with a 3x3 kernel and padding of 1, followed by batch normalisation, a ReLU activation function, and a 2x2 max-pooling layer. The number of filters increases from 32 in the first block to 256 in the fourth block, allowing the network to learn increasingly complex features. The output from the final convolutional layer is passed through a global average pooling layer, which reduces the spatial dimensions to a single vector. This vector is then processed through two fully connected layers with ReLU activations and dropout for regularisation before reaching the final classification layer with two output nodes, one for each class.

The physics-informed component is incorporated through a custom loss function (Equation 1). The total loss, , is defined as the weighted sum of the standard cross-entropy loss (

) and a physics-based regularisation term (

):

where, = hyperparameter that controls the influence of the physical constraint

The physics loss (Equation 2) is calculated as:

where, = batch size

= visual similarity for the

-th image in the batch

This term penalises low similarity between the image's content and its predicted class. The similarity score measures how well an image's dominant visual characteristics match the expected profile pattern of the predicted saturation class. This is done by extracting the image's key visual features, comparing them to a predefined template for oil or water saturation, and calculating an average match quality. A poor match yields a low similarity score, increasing the physics loss and penalising the model for predictions that violate expected visual patterns. This formulation of explicitly encourages the model to make predictions that are consistent with the known visual characteristics of the respective saturation profiles.

Model training and evaluation

The model was implemented using the PyTorch deep learning framework. The images were resized to 224x224 pixels and normalised. Data augmentation techniques, including random horizontal flipping, rotation, and colour jittering, were applied to the training set to improve model generalisation.

The model was trained using the Adam optimiser with a learning rate of 1e-6 and weight decay of 1e-7. A ReduceLROnPlateau scheduler was used to dynamically reduce the learning rate when performance plateaued. Training was monitored using early stopping to prevent overfitting. The model's performance was evaluated on the independent test set using standard metrics, including accuracy, confusion matrix, classification report (precision, recall, F1-score), and Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves with Area Under the Curve (AUC) analysis.

To provide insights into the model's decision-making process, Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) was employed. This technique generates heatmaps that highlight the regions of the input image that were most influential in the model's prediction, allowing for visual interpretation of which features the model finds important for classifying each saturation profile.

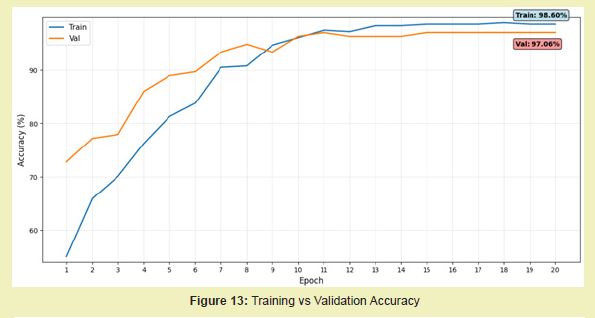

Model training performance

The training process was highly effective, as shown by the learning curves in Figure 13. The model rapidly learned from the training data, with the training accuracy increasing to a final accuracy of 98.60% within a training time of 1400s. More importantly, the validation accuracy which measures performance on unseen data during training, reached 97.06%. This demonstrates that the model generalised well without overfitting to the training data.

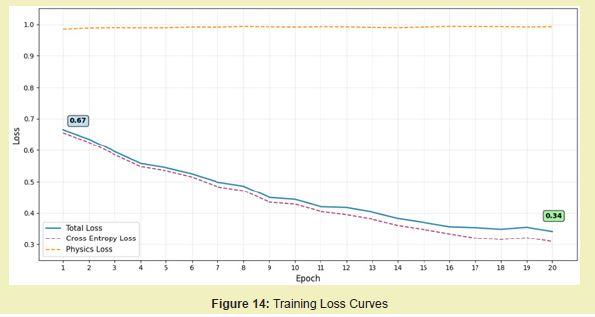

The loss curves, illustrated in Figure 14 provide further insight into the training dynamics. The total loss, which combines the standard cross-entropy loss and the physics-informed loss component, decreased steadily from 0.67 to 0.34. The consistent contribution of the physics loss throughout training confirms that the custom loss function successfully integrated the physical constraint into the learning process, guiding the model towards solutions that are not only statistically accurate but also physically consistent.

Model evaluation and classification performance

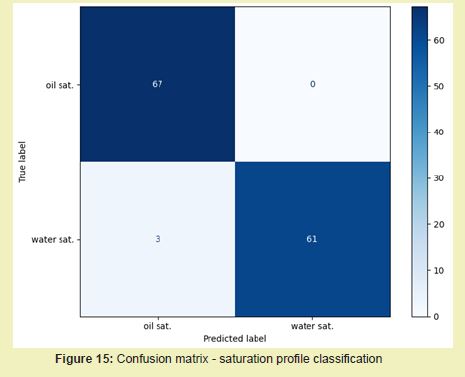

The final evaluation of the model on the independent test set of 131 images confirmed its high performance, achieving a test accuracy of 97.71%. The confusion matrix, presented in Figure 15, provides a detailed breakdown of the model's predictions. The model correctly classified 67 out of 67 oil saturation images and 61 out of 64 water saturation images. All oil saturation profiles were correctly predicted, while 3 water saturation profiles were incorrectly predicted as oil saturation.

The classification report Table 5 reinforces these findings, showing high precision and recall for both classes. The macro-average F1-score, which balances precision and recall, was 0.98, indicating robust and balanced performance across both saturation profiles.

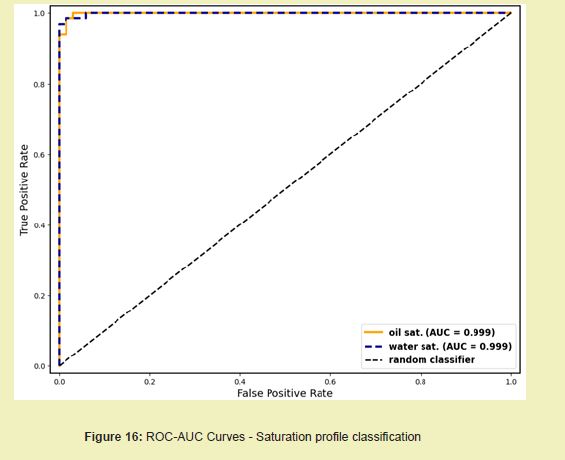

The model's strong ability to distinguish between categories is clearly shown by the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves in Figure 16 Both the oil and water saturation classes achieved an Area Under the Curve (AUC) score of 0.99. This indicates that the model exhibits ideal classification capabilities.

Interpretability of predictions

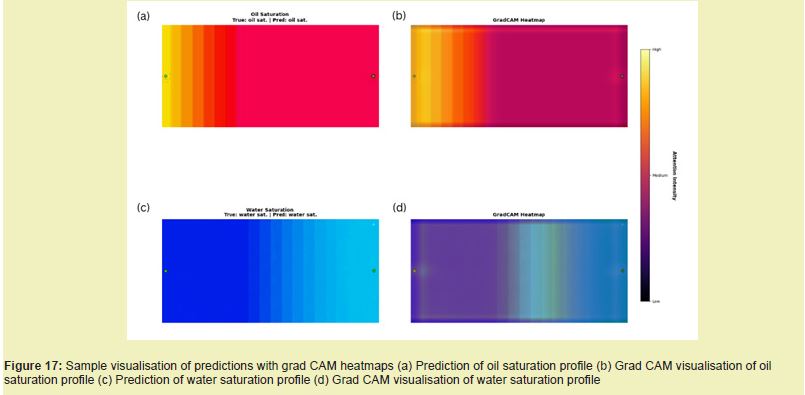

To understand the model's decision-making process, Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) was employed. This technique generates heatmaps that highlight the image regions most influential in the model's prediction. A sample visualisation is provided in Figure 17. For both oil and water saturation profiles, the Grad-CAM heatmaps show that the model focuses on distinct, relevant areas within the images rather than relying on random background features. This indicates that the model learned to identify the characteristic visual patterns associated with each physical phenomenon, validating that the physics-informed approach led to meaningful feature extraction. The high intensity in the heatmaps correlates with areas of high saturation concentration, demonstrating that the model's attention aligns well with the physically significant regions of the profiles.

This comprehensive review highlighted the critical role of numerical modelling in enhancing the filtration processes of oil droplets from produced water. The findings underscore that numerical model serve as powerful tools for simulating complex filtration dynamics, providing insights that are often unattainable through experimental methods alone. By integrating advanced computational techniques, such as computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and multiphase flow dynamics, researchers can better understand the behaviour of oil-water emulsions and optimize filtration systems for improved efficiency and effectiveness. The review also emphasizes the necessity of experimental validation to bridge the gap between theoretical predictions and real-world applications, ensuring that numerical models accurately reflect the complexities of actual filtration processes.

The optimization of the emulsion flooding model using CMOST's DE, DECE, and PSO algorithms yielded significant improvements in oil recovery and water cut performance. The base model recovered 19.0121 cm³ of oil, while the optimized models achieved up to 20.4704 cm³, with the PSO algorithm producing the highest cumulative recovery. Statistically, the DE and DECE algorithms provided an excellent fit to the data (R² = 0.9914) and resulted in smoother pressure profiles. In contrast, the PSO algorithm pursued a more aggressive optimization strategy, leading to stronger flow diversion and trapping - evident in a sharper pressure increase - though with a slightly lower statistical fit (R² = 0.9818). These results demonstrate that tuning key parameters (FREQFAC, PERMSCALE, and KRS) can enhance sweep efficiency and delay water breakthroughs. However, the aggressive parameters identified by PSO necessitate careful validation to ensure they remain within physically plausible bounds.

Looking ahead, several areas warrant further investigation to advance the field of numerical modelling in oil droplet filtration. Firstly, there is a pressing need for the development of more accurate and robust models that can account for the diverse operational conditions encountered in the oil and gas industry. This includes exploring the effects of varying fluid properties, flow rates, and environmental factors on filtration performance. Additionally, the application of machine learning algorithms in conjunction with numerical modelling presents a promising avenue for enhancing predictive capabilities and enabling adaptive filtration management systems. Future research should also focus on the integration of these models with emerging filtration technologies, such as membrane filtration and advanced materials, to promote sustainable practices and minimize the environmental impact of produced water management. By addressing these research gaps, the industry can move towards more efficient and environmentally friendly solutions for oil droplet filtration, ultimately contributing to the sustainability of oil production practices.

We would like to thank anonymous reviewers for their contributions to this research. We thank the University of Mines and Technology, Tarkwa, Ghana, GNPC Foundation, School of Petroleum Studies, and the Petroleum and Natural Gas Engineering Department for their immense support. Finally, we would like to acknowledge all authors and institutions whose article helped in shaping this research work.

This Review Article received no external funding.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

- 1. Kokal S. Crude Oil Emulsions: A State-of-the-Art Review. SPE Production & Facilities. 2005;20(1):5-13.

- 2. Abdel Raouf ME, Al Sabagh AAM, El Din MRN. Demulsification of Crude Oil Emulsions Using Ethoxylated Nonionic Surfactants. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology. 2012;33(1):1-8.

- 3. McLean JD, Kilpatrick PK. Effects of Asphaltene Aggregation in Model Heptane-Toluene Mixtures on Stability of Water-in-Oil Emulsions. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 1997;189(2):242-253.

- 4. Tian Y. The Formation, Stabilization and Separation of Oil-Water Emulsions: A Review. Processes. 2022;10(4):738.

- 5. José MH, Canejo JP, Godinho MH. Oil/water mixtures and emulsions separation methods - an overview. Materials. 2023;16(6):2503.

- 6. Fingas M, Fieldhouse B, Bobra M, et al. The physics and chemistry of emulsions. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Emulsions. Marine Spill Response Corporation; 1993:pp.11-19.

- 7. Vall Llosera M, Jessen F, Henriet P, et al. Physical Stability and Interfacial Properties of Oil in Water Emulsion Stabilized with Pea Protein and Fish Skin Gelatin. Food Biophysics. 2021;16:139-151.

- 8. Kimray. Gravity Separation. 2016.

- 9. Lim J, Wong S, Law M, et al. A Review on the Effects of Emulsions on Flow Behaviours and Common Factors Affecting the Stability of Emulsions. Journal of Applied Sciences. 2015;15(2):167-172.

- 10. Lim YJ, Lee SM, Wang R, et al. Emerging Materials to Prepare Mixed Matrix Membranes for Pollutant Removal in Water. Membranes (Basel). 2021;11(7):508.

- 11. He L, Lin F, Li X, et al. Interfacial sciences in unconventional petroleum production: From fundamentals to applications. Chemical Society Reviews. 2015;44:5446-5494.

- 12. El Naggar AMA, El-Din MRN, Mishrif MR, et al. Highly Efficient Nano-Structured Polymer-Based Membrane/Sorbent for Oil Adsorption from O/W Emulsion Conducted of Petroleum Wastewater. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology. 2014;36:118-128.

- 13. Cai Y, Chen D, Li N, et al. Nanofibrous Metal Organic Framework Composite Membrane for Selective Efficient Oil/Water Emulsion Separation. Journal of Membrane Science. 2017;543:10-17.

- 14. Chen Y, Lin M, Zhuang D. Wastewater treatment and emerging contaminants: Bibliometric analysis. Chemosphere. 2022;297:133932.

- 15. Chen H. High efficiency of nanomaterial-based filters in removing contaminants. Chemical Engineering Journal. 2018.

- 16. Karbowska B. Presence of thallium in the environment: sources of contaminations, distribution and monitoring methods. Environ Monit Assess. 2016;188(11):640.

- 17. Sundar S, Chakravarty J. Antimony toxicity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7(12):4267-4277.

- 18. Coetzee JJ, Bansal N, Chirwa EM. Chromium in Environment, Its Toxic Effect from Chromite-Mining and Ferrochrome Industries, and Its Possible Bioremediation. Exposure and Health. 2020;12:51-62.

- 19. Hou S, Yuan L, Jin P, et al. A clinical study of the effects of lead poisoning on the intelligence and neurobehavioral abilities of children. Theor Biol Med Model. 2013;10:13.

- 20. Chasapis CT, Loutsidou AC, Spiliopoulou CA, Stefanidou ME. Zinc and human health: an update. Arch Toxicol. 2012;86(4):521-534.

- 21. Rice KM, Walker EM Jr, Wu M, et al. Environmental mercury and its toxic effects. J Prev Med Public Health. 2014;47(2):74-83.

- 22. Hayat MT, Nauman M, Nazir N, et al. Environmental Hazards of Cadmium: Past, Present, and Future. In Cadmium Toxicity and Tolerance in Plants. Academic Press. 2018:pp.163-183.

- 23. Zhang X, Yang L, Li Y, et al. Impacts of lead/zinc mining and smelting on the environment and human health in China. Environ Monit Assess. 2012;184(4):2261-2273.

- 24. Zhang W, Zhu Y, Liu X, et al. Recent Progress in Superwetting Materials for Oil/Water Separation. Advanced Materials. 2019;31(7):1804508.

- 25. Shivam S, Pratik C. Futuristic Progress of Natural Emulsifiers in the Enhancement of Drug Delievery System and their Applications in Selected Medical Therapeutics. Global Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2022;10(1):555777.

- 26. Sjöblom J, Aske N, Auflem IH, et al. Our Current Understanding of Water-in-Crude Oil Emulsions. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science. 2001;100(8):399-473.

- 27. Karhu M. Treatment and characterisation of oily wastewaters. 2015.

- 28. Zhu X. High-Efficiency Oil-Water Separation Using Membrane Technology. Separation and Purification Technology. 2017.

- 29. Goh PS, Polymeric and ceramic membranes for oil-water separation. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2018.

- 30. Wang S, Pang M, Wen Z. The Structure and Property of Polyacrylonitrile-Based Microfiltration Membranes for Oil-Water Emulsion Separation. Journal of Industrial Textiles. 2022;51(5_suppl):8788S-8803S.

- 31. Wang B, Liang W, Guo Z, et al. Biomimetic Super-lyophobic and Super-lyophilic Materials Applied for Oil/Water Separation: A New Strategy Beyond Nature. Chemical Society Reviews. 2015;46(3):676-701.

- 32. Li X. Carbon nanotubes in water purification: Surface area and electrical characteristics. Environmental Science & Technology. 2020.

- 33. Smith J. Graphene-based filters for long-term filtration applications. Journal of Applied Physics. 2021.

- 34. Jones P, Nanotechnology in oil spill clean-ups and wastewater treatment. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. 2017.

- 35. Versteeg HK, Malalasekera W. An Introduction to Computational Fluid Dynamics: The Finite Volume Method. Pearson Education. 2007.

- 36. Cundall PA, Strack ODL. A Discrete Numerical Model for Granular Assemblies. Géotechnique. 1979;29(1):47-65.

- 37. Zienkiewicz OC, Taylor RL, Zhu JZ. The Finite Element Method: Its Basis and Fundamentals. Elsevier; 2005.

- 38. Bathe KJ. Finite Element Procedures. Prentice Hall. 1996.

- 39. Reddy JN. An Introduction to the Finite Element Method. McGraw-Hill; 2006.

- 40. Bear J. Dynamics of Fluids in Porous Media. Dover Publications. 1972.

- 41. Blunt MJ. Flow in Porous Media - Pore-Network Models and Multiphase Flow. Current Opinion in Colloid and Interface Science. 2001;6(3):197-207.

- 42. del Carmen Mendez Z. Flow of dilute oil-in-water emulsions in porous media [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin]. 1999.

- 43. Hwang J, Sharma MM. Generation and filtration of O/W emulsions under near-wellbore flow conditions during produced water re-injection. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering. 2018;165:798-810.

- 44. Moghadasi J, Müller-Steinhagen H, Jamialahmadi M, et al. Theoretical and experimental study of particle movement and deposition in porous media during water injection. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering. 2004;43(3-4):163-181.

- 45. Iliev O, Laptev V. On numerical simulation of flow through oil filters. Computing and Visualization in Science. 2004;6:139-146.

- 46. Zarin T, Aghajanzadeh M, Riazi M, et al. Experimental and Numerical Study of the Water-In-Oil Emulsions in Porous Media. Capillarity. 2024;13(1):10-23.

- 47. Yu L, Ding B, Dong M, et al. A new model of emulsion flow in porous media for conformance control. Fuel. 2019;241:53-64.

- 48. Soo H, Radke CJ. The flow mechanism of dilute, stable emulsions in porous media. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Fundamentals. 1984;23(3):342-347.

- 49. Sadeghinia A, Mehranbod N. CFD simulation and experimental validation of oil-in-water emulsion flow on CT images of a sand filter medium: Impact of pore morphology on trapping phenomena. Chemical Engineering Research and Design. 2025;222:452-467.

- 50. Marchesin D, Alvarez AC, Hime G, et al. Determining the Filtration and Permeability Reduction Functions for Flow of Water with Particles in Porous Media. In: ECMOR X-10th European Conference on the Mathematics of Oil Recovery. European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers. 2006:pp.cp-23.

- 51. Demikhova II, Likhanova NV, Perez JRH, et al. Emulsion flooding for enhanced oil recovery: Filtration model and numerical simulation. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering. 2016;143:235-244.

- 52. Azizov I, Dudek M, Øye G. Studying droplet retention in porous media by novel microfluidic methods. Chemical Engineering Science. 2022;248(2):117152.

- 53. Soma J, Papadopoulos KD. Flow of Dilute, Sub-Micron Emulsions in Granular Porous Media: Effects of pH and Ionic Strength. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 1995;101(1):51-61.

- 54. Pouraria H, Park KH, Seo Y. Numerical modelling of dispersed water in oil flows using eulerian-eulerian approach and population balance model. Processes. 2021;9(8):1345.

- 55. Kpeglo DO, Mantero J, Darko EO, et al. Radiochemical characterization of produced water from two production offshore oilfields in Ghana. Journal of Environmental Radioactivity. 2016;152:35-45.

- 56. Kyrloglou A, Giefer P, Fritsching U. Numerical simulation of droplet dispersion within meso-porous membranes. Frontiers in Physics. 2024;12.

- 57. Kooti G, Dabir B, Taherdangkoo R, et al. Modelling droplet size distribution in inline electrostatic coalescers for improved crude oil processing. Scientific Reports. 2023;13(1):20209.

- 58. Saleh SN, Barghi S. CFD Simulation of the Interaction Between a Macrobubble and a Dilute Dispersion of Oil Droplets in Quiescent Water. Clean Technologies. 2025;7(3):65.

- 59. Hafsi Z, Elaoud S, Mishra M, et al. Numerical Study of Droplets Coalescence in an Oil-Water Separator. Conference paper. Advances in Mechanical Engineering, Materials and Mechanics. 2020:pp.449-454.

- 60. Fazlifard S, Mostafayi SS, Ronaghi TB. 3-Dimensional CFD Simulation of Pre-Wastewater Treatment via Multi-Channel Porous Ceramic Membrane, European Journal of Engineering and Technology Research. 2024;9(1):66-71.

- 61. Iryna I Demikhova, Natalya V Likhanova, Joaquin R Hernandez Perez, et al. Emulsion flooding for enhanced oil recovery: Filtration model and numerical simulation. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering. 2016;143:235-244.

- 62. Raissi M, Perdikaris P, Karniadakis GE. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. Journal of Computational Physics. 2019;378:686-707.