Produced Water (PW), a major component of well effluents during petroleum production, often contains contaminants such as toxic Heavy Metals (HMs). Usage of inorganic chemicals for PW treatment has environmental impacts and has been reported to be ineffective in reducing concentrations of HMs to recommended standards. There is dearth of information on the usage of organic materials in PW treatment because they are insufficiently investigated. This study was therefore designed to evaluate the effectiveness of modified Cashew Nut Shells (CNS), Banana Stems (BS) and Unripe Banana Peels (UBP) for treating PW from Niger Delta. A constructed adsorption column of 1.0 m height and 0.4 m internal diameter was retrofitted with a 0.2 hp pump. The CNS samples obtained from a local market were broken manually, washed with distilled water and acetone, and oven-dried at 105℃ (24 hours). Pulverized (<2.0 mm) Non De-oiled CNS (NDCNS) was sieved (2.54 mm), soaked and de-oiled with hexane to obtain De-oiled CNS (DCNS). Resulting NDCNS and DCNS were modified (6 hours) with 0.001M NaOH (1:10 (m/v)) using magnetic stirrer (150 rpm, 60℃) and rinsed. The BS and UBP were washed, sun-dried (48 hours) and pulverised to obtain BS Powder (BSP) and UBP Powder (UBPP), respectively, using standard methods. The BSP and UBPP were modified with (1:20 (m/v)) NaOH. Bio-chars of NDCNS, DCNS, BSP and UBPP were produced by oven-pyrolysis at 300℃ (3 hours). Untreated PW samples obtained from Niger Delta were analyzed for HMs using Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (AAS), treated under batch process and re-analyzed with adsorption isotherms. Data were analyzed using ANOVA at α_0.05. The PW contained chromium (0.054±0.014 ppm), nickel (0.550±0.020 ppm), iron (6.110±0.190 ppm) and lead (0.059±0.016 ppm). Batch treatment reduced HMs concentrations by 13.0-66.7, 74.0-93.5, 91.0-95.7 and 55.9-96.6% for unmodified and 13.0-81.5, 77.1-95.5, 91.6-98.3 and 67.8-94.6% for modified NDCNS, DCNS, BSP and UBPP, respectively. Reduction in HMs concentrations of 1.90-90.7, 75.6-97.5, 94.1-99.4 and 71.2-98.3% were obtained using bio-chars of NDCNS, DCNS, BS and UBP, respectively. Optimum time for chemical modification of adsorbents was 2 hours. The DCNS performed better than NDCNS. Modified adsorbents performed better than unmodified. Adsorbents with high dosage (5 g) were more effective. Langmuir isotherm better described adsorption of nickel (R²=0.982) and lead (R²=1.000), while Freundlich isotherm better described adsorption of chromium (R²=0.921). Modified cashew nut shells, banana stems and unripe peels effectively removed heavy metals from produced water in Niger Delta oil field. Hence, they have potential to replace imported inorganic chemicals if used at some optimal conditions.

Keywords: Produced water, Heavy metals adsorption, Bio-adsorbents, Bio-char

Abbreviations: PW: Produced Water; HM: Heavy Metals; CNS: Cashew Nut Shells; DCNS: De-oiled CNS; NDCNS: Non de-oiled CNS; BSP: Banana Stems Powder; UBPP: Unripe Banana Peels Powder; BSB: Banana Stems Bio-char; DCB: De-oiled CNS Biochar; NDCB: Non de-oiled CNS Bio-char; UBPB: Unripe Banana Peel Bio-char; AC: Industrial Activated Carbon; AAS: Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer

Produced Water (PW) is the largest effluent during petroleum production operations.1 It may contain heavy metals, chemicals and sometimes radioactive materials, which can potentially put the environment at risk. It is a by-product generated during extraction of oil and gas from underground reservoirs. Produced Water results in negative environmental impacts when it is not properly managed.2 Managing produced water remains critical due to the large volumes involved, treatment costs, and environmental consequences.3,4 In Nigeria, it has been observed that approximately one billion barrels of water are disposed annually from oil and gas production activities (Isehunwa and Onovae, 2011). The bulk of PW comes from the aquifer that usually underlies the oil and gas reservoirs. Occasionally, PW could come from water injected during secondary recovery. Produced water may contain hazardous organic and inorganic pollutants, making it unsuitable for direct discharge into the environment. Uncontrolled discharge can lead to environmental damage, harming aquatic organisms and plant life. Proper management of produced water ensures it meets quality standards set by World Health Organization (WHO) and Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission5 before PW will be discharged into the environment.

Adsorption is often regarded as superior to other wastewater treatment techniques due to its low cost, easy accessibility, straightforward design, high efficiency, and ease of operation. It is fundamentally a surface phenomenon where substrate molecules accumulate on the surface. In a typical adsorption process, a foreign substance in either gaseous or liquid form (the adsorbate) adheres to a solid surface (the adsorbent), resulting in formation of an adsorptive. Molecules on the adsorbent's surface experience intermolecular interactions, leading to adsorption of adsorbate onto the adsorbent.6 Several factors influence adsorption, including the pH of the solution, contact time, solution concentration, quantity of adsorbent, temperature, and particle size. Current conventional treatment technologies focus on removing grease, HM, suspended solids and desalinating produced water.7 However, these processes can generate large volumes of secondary waste, such as sludge from heavy metal removal. The types and concentrations of contaminants in produced water heavily influence the most suitable methods for beneficial reuse, as well as the extent and cost of necessary treatment. Some produced water types require multiple treatment technologies for effective contaminant removal, necessitating selection criteria to refine the options.8 Adsorption isotherm describes the relationship between the amount of material adsorbed onto an adsorbent and the equilibrium concentration in the solution at a constant temperature. This equilibrium is achieved when the adsorbate and adsorbent interact for a sufficient time, allowing the interface concentration to dynamically balance with the concentration of the adsorbate in the bulk solution.

Mohammed9 researched the removal of cyanide from wastewater using banana peels. Their study assessed the effectiveness of banana peels in adsorbing cyanide ions from simulated synthetic aqueous solutions. The maximum removal efficiency reached 95.65% for cyanide ions. Muhammad10 examined the low-cost bio-sorption of heavy metals using banana peels as an adsorbent for extracting metal ions (lead, copper, zinc, and nickel) from wastewater. The results demonstrated a significant reduction in the concentration of the metals to acceptable levels. Boadu11 conducted comparative analysis of physicochemical properties of the activated carbon derived by using palm kernel, coconut, and groundnut shells. Results showed that activated carbon from these materials possessed desirable physicochemical properties and adsorption capabilities. Ronny12 utilised banana stem charcoal as an adsorbent to reduce the presence of metals (iron, manganese, calcium, and magnesium) which contribute to water hardness. The adsorption process using banana stem charcoal successfully reduced water hardness by 43.56% over a contact time of 240 minutes. Yousef13 reviewed the main issues related to produced water and recent adsorption applications for its treatment, distinguishing between natural and synthetic adsorbents. The study further used various adsorption isotherm models to describe these applications.

The materials used in this study included: Niger delta PW samples X and Z, Cashew Nut Shells (CNS), banana stems, unripe banana peels, chemical reagents, distilled water, funnels, beakers, filter papers, yeast, potato dextrose broth, brown paper, plastic bottles, hand gloves and masking tape. Equipment used included: pH meter, laboratory oven, atomic absorption spectrophotometer, weighing balance, sieves, soxhlet extractor, magnetic stirrer, industrial-oven and grinder. Cashew nut shells, obtained from a local market, were broken to remove the nuts present using a manual breaker. The broken shells were washed with distilled water, followed by an acetone wash. These washed CNS were dried in laboratory-oven at 105°C for 24 hours, pulverized using a grinder and sieved (2.54 mm sieve mesh size) to maintain standard size. This made up the non de-oiled CNS (NDCNS) sample. Portion of NDCNS was extracted with hexane, after soaking it in n- hexane for 24 hours, by using the soxhlet extractor to remove CNS black oil, and the remaining drained CNS was dried at room temperature to make up the de-oiled cashew nut shells (DCNS) sample. Samples of PW were poured on unmodified DCNS and NDCNS of 1g and 5g each on funneled filter paper inside beaker for batch adsorption process to take place. The filtrates were put in labeled sampling bottles for AAS analysis in the laboratory.

Chemical modification was carried out by immersing separately NDCNS and DCNS samples in 0.001M of NaOH solution at the rate of 1:10 (m/v) plus constant stirring of 150rpm and 60℃ by using magnetic stirrer. Portions of the treated DCNS and NDCNS samples were obtained separately on hourly basis (1 to 3hours), washed with distilled water to remove excess modifying solution. Resulting samples were dehydrated for 20 minutes in laboratory-oven (40℃). Modified NDCNS and DCNS were separately measured (1g and 5g each) on funneled filter paper inside beaker and treated with produced water samples, for batch adsorption process. Portions of NDCNS and DCNS samples were pyrolysed in an industrial-oven at 300℃ for 3 hours. The resulting contents were ground to powdery form using a grinder. NDCNS bio-char (NDCB) and DCNS bio-char (DCB) of 1g and 5g each was treated with produced water for batch adsorption. The filtrates resulting were bottled, labeled and sent for AAS analysis.

The banana stems and unripe banana peels were sourced from a local market, washed with distilled water, cut and sliced into pieces for easy and fast sun-drying for 48 hours (during dry season). A portion of these samples were ground into powder and sieved to have banana stems powder (BSP) and unripe banana peels powder (UBPP). Second Portion of the samples was pyrolysed in an industrial-oven at 300℃ for 3 hours. The resulting contents were ground to powdery form to have banana stem bio-char (BSB) and unripe banana peels bio-char (UBPB). Unmodified BSP and UBPP samples were measured separately, 1g and 5g each, on funneled filter paper inside beaker and untreated samples of PW were poured on them for batch adsorption process to take place. The filtrates were put in labeled sampling bottles for AAS analysis in the laboratory. The BSB and UBPB of 1g and 5g dosages were also treated with PW samples for batch adsorption. The resulting filtrates were labeled and sent for AAS analysis. Chemical modification was done on BSP and UBPP using 0.001M NaOH with the rate 1:20 (m/v) alongside constant stirring of 150 rpm and 60℃ by using magnetic stirrer as it was done for chemically modified CNS. On hourly basis (1 to 3hours), portions of these samples were obtained, washed with distilled water and dried in laboratory-oven (40℃) for 20minutes Modified NDCNS and DCNS were separately measured (1g and 5g each) on funneled filter paper inside beaker and treated with produced water samples, for batch adsorption process; while the resulting filtrates were taken for AAS analysis.

Values obtained from modifying DCNS and BSP in varying hours, were used to calculate the linear equation terms in the adsorption isotherm models, in order to ascertain the model which will be suitable for equilibrium study of dissolved metals in the produced water. Adsorption isotherms’ models used in this research were those of Langmuir and Freundlich, in analyzing equilibrium performance of adsorption system at constant temperature. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy Disperse Spectroscopy (EDS) analyses were carried out on samples by using Axia ChemiSEM thermoscientific 2023 model machine, in order to determine their physical and chemical properties, which can inform their potential applications and also, elemental compositions.

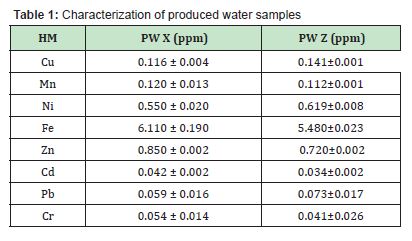

Characterization of produced water from AAS analysis

Analysis of metal ions present in the produced water samples is given below Table 1:

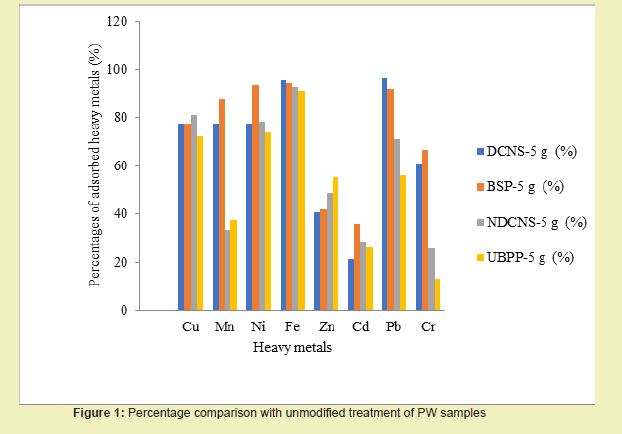

Treatment of Produced Water with Unmodified Samples:

Considering the results shown in Figure 1, percentage reductions in heavy metal concentrations using unmodified DCNS were found to range from 21.4% to 98.9%, 25.9% to 92.6% with unmodified NDCNS, 35.7% to 99.5% using unmodified BSP and 13.0% to 91.0% with unmodified UBPP. The results revealed that treatment with 5g of unmodified adsorbents gave the best reductions in heavy metal concentrations compared with treatment using 1g of unmodified adsorbents, and this was because larger surface areas of adsorbent would improve adsorption process. The experimental results revealed that this study unmodified adsorbents have potential to reduce toxic heavy metals in produced water, as reductions in concentrations were observed in all heavy metals. The analysis of these unmodified adsorbents revealed that unmodified BSP gave the best treatment. This study had better results (Cu=81%, Ni=93.5%, Zn=55.3%, Pb=96.6%) than the results of Oboh and Aluyor,14 who used unmodified sour sop seeds (Cu=77.6%, Ni=68.5%, Zn=56.4%, Pb=40.6%) in their heavy metals’ removal.

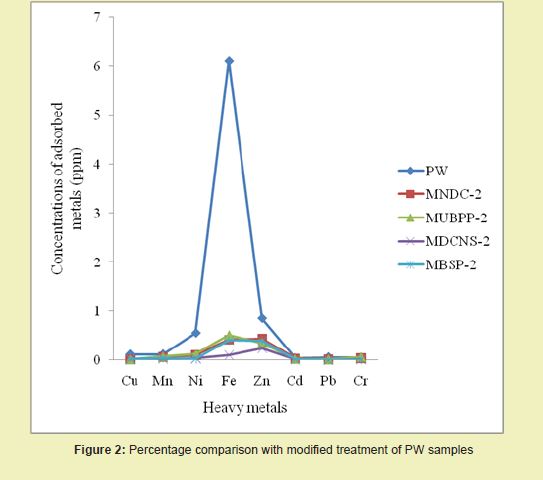

Treatment of Produced Water with Chemically Modified Samples

Experimental results showed that the optimum treatment of produced water with modified adsorbents was obtainable at 2 hours of chemical modification, after which desorption set in. Figure 2 showed that modified DCNS gave the best treatment among the four modified adsorbents, followed by modified BSP, NDCNS and UBPP. All modified adsorbents performed better in the removal of heavy metals than their unmodified states. This study’s results were in agreement with Sciban,15 who also used NaOH modification to boost the adsorption efficiency.

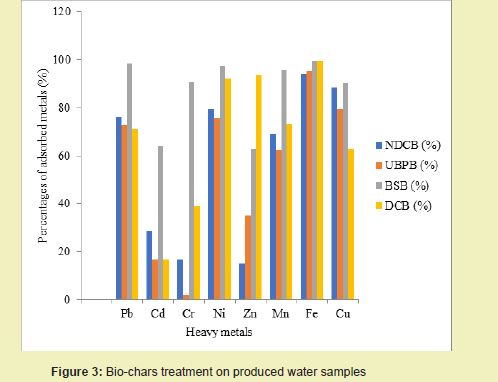

Treatment of Produced Water with Bio-char Samples

Figure 3 compared the percentage reductions in heavy metals’ concentrations after treatment with adsorbent bio-chars. Results with BSB treatment on PW gave the best among the selected bio-chars because it had micro-pores and macro-pores (SEM analysis), which accounted for its efficient specific surface areas. Moreover, BSB had oval-like holes accounting for its irregular porous surface, which helped in its affinity for heavy metals adsorption. This study results (Zn=93.7%, Cu=90.5%, Ni=97.5% and Fe=99.4%) were more efficient than the results obtained by Akinsete, et al.16 in which their highest adsorption values were: Zn=86%, Cu=88%, Ni=55% and Fe=52%; despite the Phosphoric acid impregnation done which could have added more cost to the treatment and could end up having environmental impacts.

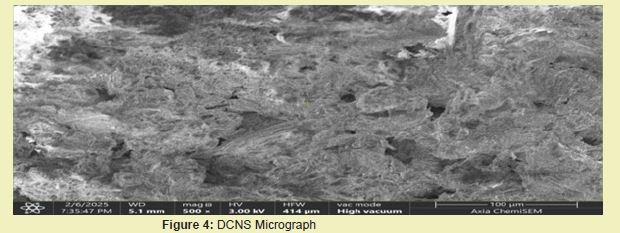

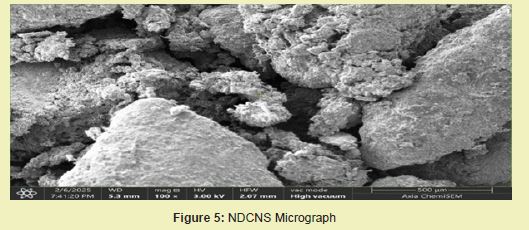

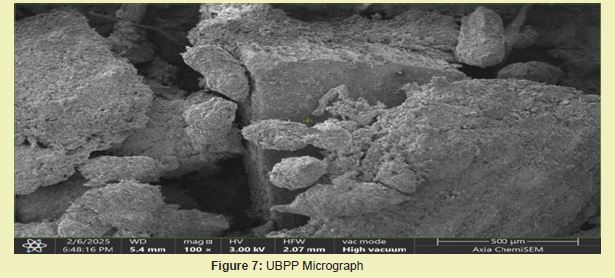

Micrographs of adsorbents from SEM analysis

Both DCNS Figure 4 and NDCNS Figure 5 had rough and porous surfaces with compact structure from their SEM images, except that DCNS had smoother surface texture and better surface area. And this was the reason for DCNS better adsorption efficiency than NDCNS. The BSP Figure 6 revealed a more compact, less porous structure and smooth surface compared to BSB from its SEM image, reason for its lesser efficiency. The UBPP Figure 7 from its SEM image showed a mixture of smooth and rough surfaces which were more compact, with higher moisture content; and hence, reason for its low adsorption capacity. Results for BSB treatment gave the best results among the bio-chars used because it showed a highly porous structure with a rough surface, indicating a very high surface area from its SEM image Figure 8.

Analysis Using Adsorption Isotherm Models

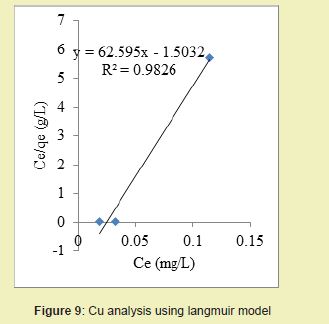

Experimental results obtained after treating the produced water samples with chemically modified DCNS were used for the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models in order to analyse the sorption process of each heavy metal.

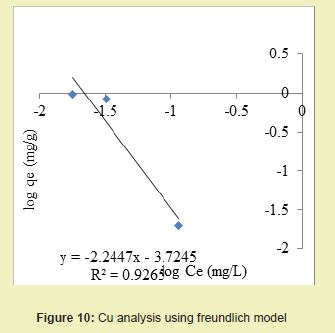

Considering the linear graph plots Figures 9 and 10, it was shown that the correlation coefficients (R2) for Cu ion were 0.982 and 0.926 for Langmuir and Freundlich models respectively. It suggested that adsorption process for Cu ion obeyed Langmuir model. This finding suggested that Langmuir model was more suitable for equilibrium studies of Cu ion than Freundlich model.

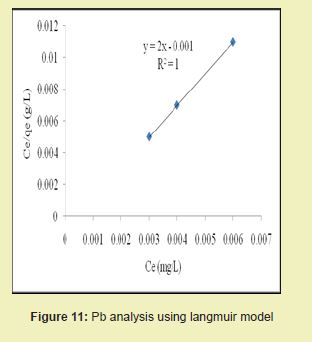

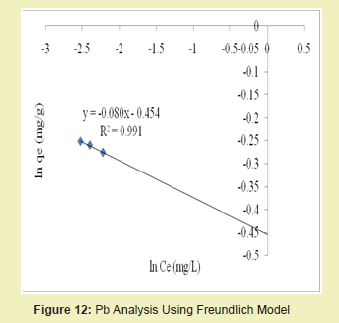

The graphical representations of results considering Figures 11 and 12 above showed that the correlation coefficients (R2) for Pb ion were 1 and 0.991, respectively. It suggested that adsorption process for Pb ion obeyed Langmuir model. This finding suggested that Langmuir model was more suitable for equilibrium studies of Pb ion than Freundlich model.

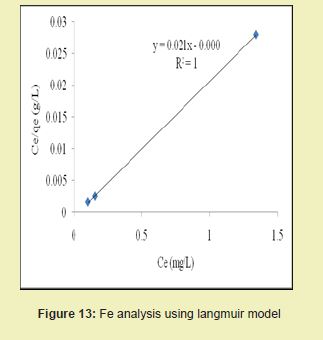

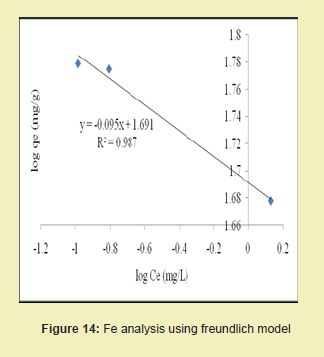

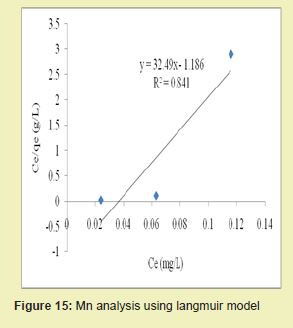

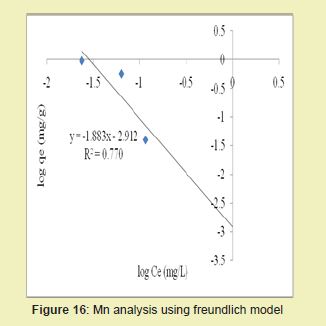

Figures 13 and 14 showed graphical representations of the isotherm results for Fe. Considering the linear graph plots, showed that the correlation coefficients (R2) for Fe ion were 1 and 0.987, respectively. It suggested that adsorption process for Fe ion obeyed Langmuir model. This finding suggested that Langmuir model was more suitable for equilibrium studies of Fe ion than Freundlich model. The correlation coefficients (R2) for Mn ion as seen in Figures 15 and 16 were 0.841 and 0.770, respectively. It suggested that adsorption process for Mn ion obeyed Langmuir model. This finding suggested that the Langmuir model was more suitable for equilibrium studies of Mn ion than the Freundlich model. Furthermore, the results indicated that Mn ions exhibit monolayer coverage of adsorbate on bio-adsorbent surface.

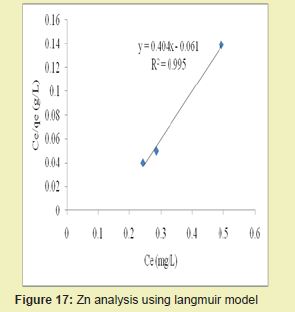

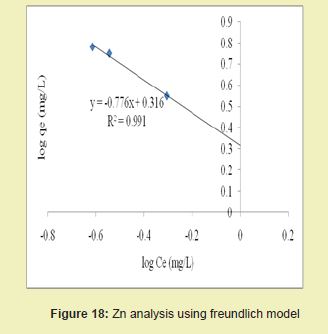

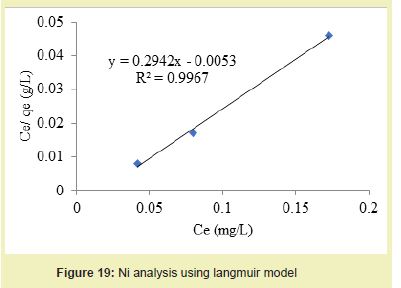

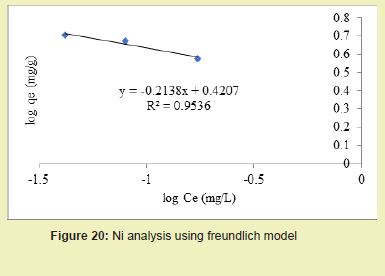

Considering the linear graph plots for Zn in Figures 17 and 18, showed that correlation coefficients (R2) for Zn ion were 0.995 and 0.991, respectively. It suggested that adsorption process for Zn ion obeys Langmuir model. This finding suggested that Langmuir model was more suitable for equilibrium studies of Zn ion than the Freundlich model. Figures 19 and 20 showed the correlation coefficients (R2) for Ni ion were 0.982 and 0.926, respectively. It suggested that adsorption process for Ni ion obeyed Langmuir model. This finding suggested that Langmuir model was more suitable for equilibrium studies of Ni ion than Freundlich model.

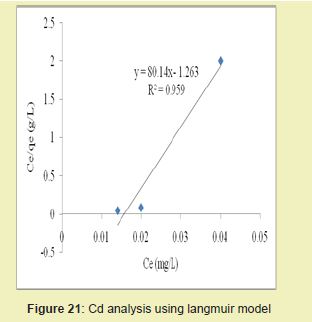

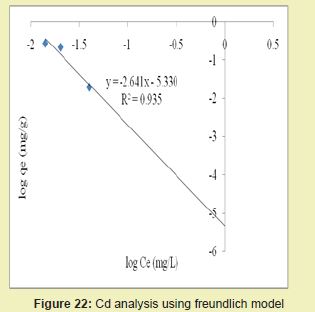

Figures 21 and 22 showed the graphical representations of the results from the analysis of Cd by using both the Langmuir and Freundlich models for modified DCNS. The linear graph plots showed that correlation coefficients (R2) for Cd ion were 0.959 and 0.935, respectively. It suggested that adsorption process for Cd ion obeyed Langmuir model. This finding suggested that Langmuir model was more suitable for equilibrium studies of Cd than Freundlich model.

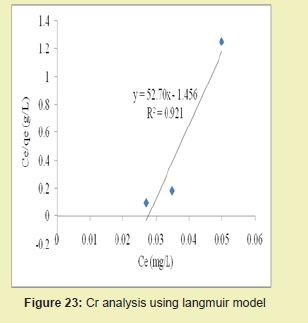

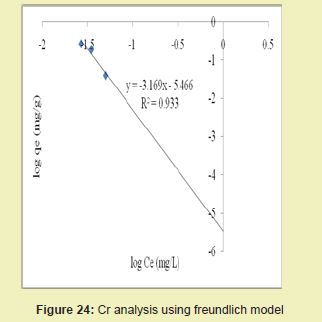

Figures 23 and 24 showed graphical representations of the results of the analysis of Cr using both the Langmuir and Freundlich models for modified DCNS. Considering the linear graph plots, showed that correlation coefficients (R2) for Cr ion were 0.921 and 0.933, respectively. It suggested that adsorption process for Cr ion obeyed Freundlich model. This finding suggested that Freundlich model was more suitable for equilibrium studies of Cr ion than Langmuir model.

Comparison of present work with past research works

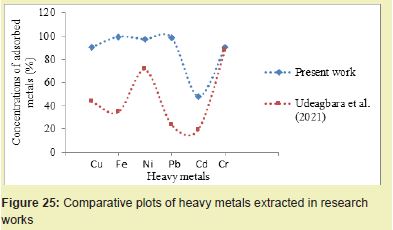

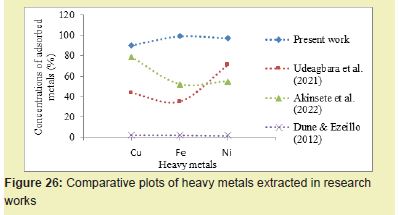

The BSB of 5g extracted 98.31% Pb from the PW, which was better than the method of Udeagbara17 which extracted 23.48% Pb Figure 25. BSB treatment extracted 90.52% Cu from PW, unlike Akinsete16 method which extracted 88% Cu, Dune and Ezeillo18 method that removed 2.15% Cu and Udeagbara17 method which extracted 43.65% Cu Figure 26. BSB treatment extracted 99.43% Fe from PW compared to Akinsete method which extracted 52% Fe. The BSB treatment method extracted 97.45% Ni from PW while Udeagbara17 extracted 71.42% and Akinsete16 extracted 55%. These stated observations indicated that BSB adsorbent has more adsorption efficiency in heavy metals extraction from PW than any other existing adsorbents.

Unmodified non de-oiled and de-oiled cashew nut shells, banana stems powder and unripe banana peels powder have potentials to remove heavy metals substantially in produced water. This study showed that larger surface area of adsorbents would improve adsorption process. Unmodified banana stems powder performed best among others in the removal of heavy metals. Chemically modified non-de-oiled and de-oiled cashew nut shells, banana stems powder and unripe banana peels powder have better potentials to remove heavy metals in produced water than the unmodified, under a batch process. The study showed that the time used for chemical modification could affect modified bio materials; with optimum treatment of metal extraction from produced water obtained at two hours of chemical modification, after which desorption set in. Chemical modification on bio-materials gave longer shelf life to modified bio-materials compared to unmodified bio-materials. Modified bio-materials would biodegrade slower than unmodified bio-materials due to chemical modification. Modified de-oiled cashew nut shells performed best among others. Non de-oiled and de-oiled cashew nut shells bio-char, banana stems bio-char and unripe banana peels bio-char have the highest adsorption efficiency for the removal of heavy metals in produced water both in batch process. Banana stems bio-char performed best among all other bio-chars. The adsorption isotherms used to analyse the sorption process of each heavy metal in the produced water showed that Langmuir isotherm explained nickel, lead, cadmium, copper, iron, manganese and zinc; while chromium performed better under Freundlich isotherm description. Thus, banana stem bio-char has the most effective adsorption strength to treat produced water for optimal extraction of heavy metals before it is disposed into the marine environment or re-used for water flooding and other benefits.

The content of this paper article is genuine and not copyright. The use of selected organic materials, which are agricultural wastes (cashew nut shells, banana stems and unripe banana peels) in the efficient and cheap treatment of produced water. The authors take full responsibility for the originality of the article.

Authors of this paperwork did not use generative AI or AI – assisted technologies in the course of this work, in order to ensure confidentiality of the research.

The authors appreciate the assistance rendered by the technologists in the Production Laboratory of the Department of Petroleum Engineering, University of Ibadan, Nigeria.

This research did not receive any specific grant or other support from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors during the preparation of this manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

- 1. Isehunwa SO, Onovae S. Evaluation of produced water discharge in the Niger Delta. Journal of Engineering and Applied Science. 2011;6(3):66-72.

- 2. Bashir I, Lone FA, Bhat RA, et al. Concerns and Threats of Contamination on Aquatic Ecosystems. Bioremediation and Biotechnology. 2020:1-26.

- 3. Breit G, Klett TR, Rice CA, et al. National compilation of information about water co-produced with oil and gas. 5th International Petroleum Environmental Conference, Albuquerque, NM. 1998:pp.20-23.

- 4. Hackney J, Wiesner MR. Cost assessment of produced water treatment. 1996.

- 5. Department of Petroleum Resources. Environmental guidelines and standards for the petroleum industry in Nigeria. Department of Petroleum Resources, Ministry of Petroleum and Mineral Resources, Lagos. 1991.

- 6. Zhu CS, Wang LP, Chen WB. Removal of Cu (II) from aqueous solution by agricultural by-product: Peanut hull. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2009;168:739-746.

- 7. Macêdo Júnior RO, Serpa FS, Santos BLP, et al. Produced water treatment and its green future in the oil and gas industry: a multi-criteria decision-making study. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology. 2022;20:1369-1384.

- 8. Mousa KM, Arafat AS. Experimental study on treatment of produced water. Journal of Chemical Engineering Process Technology. 2015;6:261-271.

- 9. Mohammed NA, Firas SA, Suha AI. Cyanide removal from wastewater by using banana peels. Journal of Asian Scientific Research. 2014;4.5:239-247.

- 10. Muhamed AA, Karamat M, Abdul W. Study of low cost bio-sorption for heavy metals. International Conference on Food Engineering and Biotechnology. IACSIT Press. 2011;9:45-58.

- 11. Boadu KO, Joel OF, Essumang DK, et al. Comparative studies of the physicochemical properties and heavy metals adsorption capacity of chemical activated carbon from palm kernel, coconut and groundnut shells. Journal of Applied Science, Environment and Management. 2019;22(11):1833-1839.

- 12. Ronny I, Mahyudin , Jasman A. Banana stem charcoal as adsorbents to reduce water hardness levels. International Journal of Environment, Engineering and Education. 2019;1(1):1-6.

- 13. Yousef R, Qiblawey H, El Naas MH. Adsorption as a process for produced water treatment: A Review. Department of Chemical Engineering, Qatar University, 2020:pp.1657-1679.

- 14. Oboh OI, Aluyor EO. The removal of heavy metal ions from aqueous solutions using sour sop seeds as bio-sorption. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2008;7:24-30.

- 15. Sciban M. Modified hardwood sawdust as adsorbent of heavy metal ions from water. Wood Science Technology. 2006;40:217-227.

- 16. Akinsete OO, Agbabi PO, Akinsete SJ, et al. Comparative study of improved treatment of oil produced-water using pure and chemically impregnated activated carbon of banana peels and Luffa cylindrical. African Journal of Environment, Science and Technology. 2022;16(12):422-431.

- 17. Udeagbara SG, Isehunwa SO, Okereke NU, et al. Treatment of produced water from Niger Delta oil fields using simultaneous mixture of local materials. Journal of Petroleum Exploration and Production Technology. 2021;11:289-302.

- 18. Dune KK, Ezeillo FE. Performance evaluation of a water hyacinth-based sewage treatment system. New Era Research Journal of Education, Human and Sustainable Development. 2012;10:26-34.